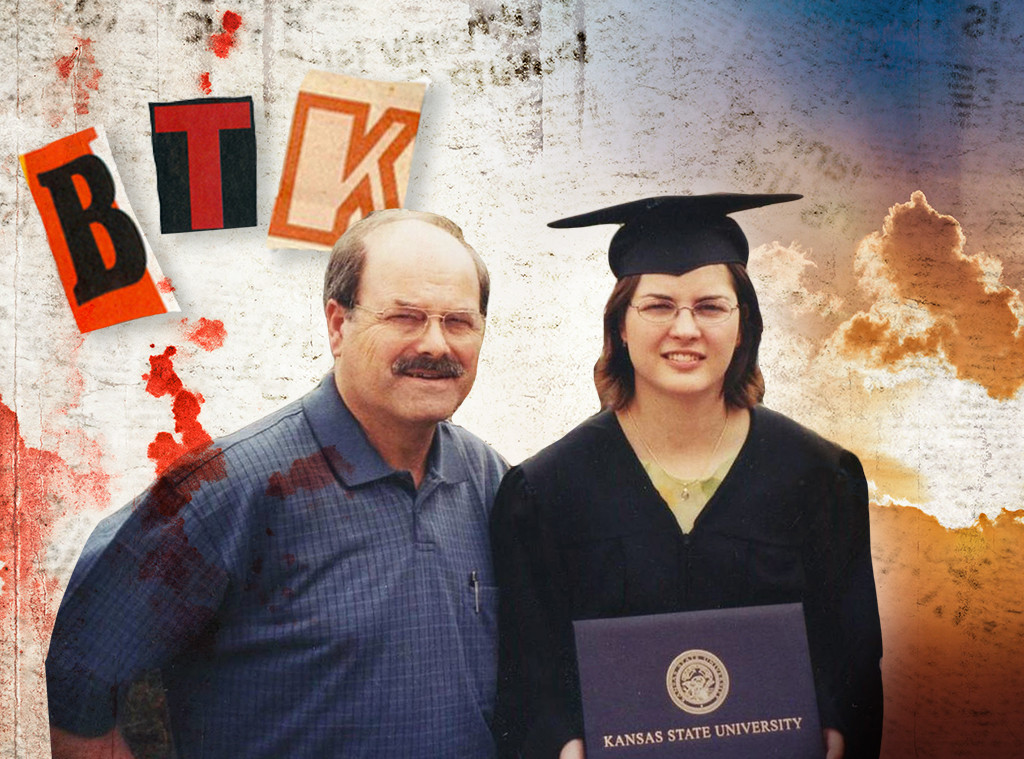

Kerri Rawson; E! Illustration

In the summer of 2004, a Michigan-based substitute teacher was scrolling through ABCNews.com when an intriguing story caught her eye. It had been more than 30 years since a still-unknown serial killer had ended the lives of Kansas couple Joseph Otero and Julie Otero and their children Josie, 11, and Joey, 9, in January of 1974 and her hometown newspaper, the Wichita Eagle, had decided to commemorate their loss with a story.

One line in the article—a mention that the legacy of the killer had long been forgotten—apparently angered the murderer so much that he decided to send a letter, enclosing the photo of one of his victims. His intention was to spark people’s memories and it worked. For months local outlets were publishing stories that the ruthless killer had re-emerged after decades of silence.

There was much to discuss, what with his decision to claim responsibility for another murder, and resume his old ploy of taunting both the media and police alike with clues on how he’d gotten away with his crime spree.

The development turned the cold case into a massive manhunt and left Kerri Rawson thoroughly intrigued. Though she’d grown up in the midwestern town at the time, this was the first she’d heard of the unsolved mystery. She was taken aback that something like this was happening in the background of her largely idyllic childhood. Still, she assumed, as she’d later relay to 20/20 cameras that the guy was just some law-breaking miscreant, “a loner.”

Never once did she imagine he was her father. The psychopath who dubbed himself BTK—an acronym depicting his preferred method of murder: Bind, Torture, Kill—couldn’t possibly be the same man who allowed her to dance on his stocking-covered feet as a child and served as the president of his church and a Boy Scout troop leader.

And yet not nine months after she began studying up on the case that had terrorized her hometown for some three decades she found herself face-to-face with an FBI agent. He’d traveled to the Detroit-area apartment she shared with her husband the afternoon of Feb. 25, 2005 to inform her that they’d used her own DNA to confirm their suspicions. Her dad had been arrested as BTK.

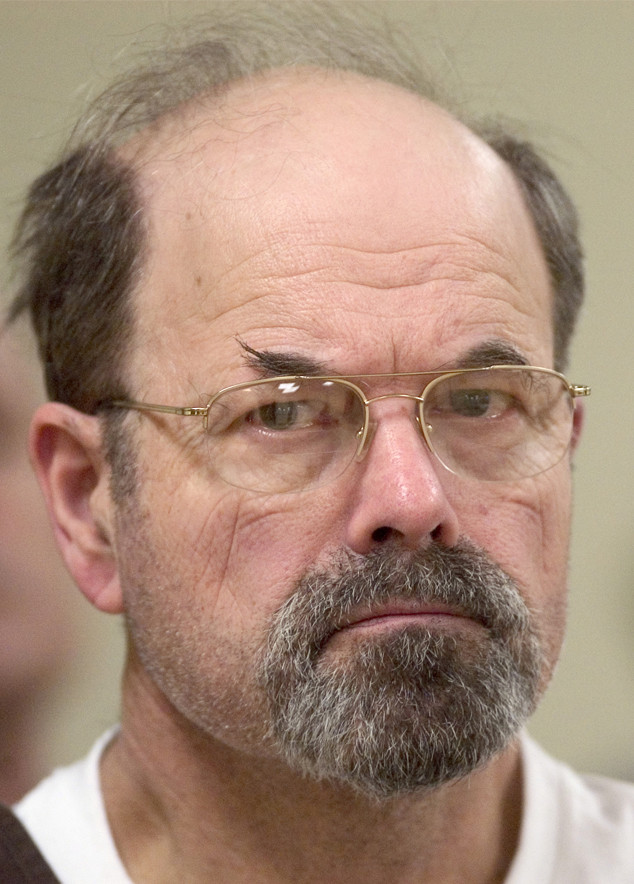

Travis Heying/Wichita Eagle/TNS via Getty Images

“I was gripping the wall next to my stove, [the room] was spinning, [I was] saying, ‘I think I’m going to pass out,'” she recalled to ABC News’ 20/20 for their Feb. 1 special detailing the murderer’s reign of terror. “[The agent] was asking me questions about my dad, about dates and things, and I was…trying to almost alibi my father. I was like, ‘My father is a good guy. He’s, like, Boy Scout leader, president of the church. You’ve got the wrong man.'”

They didn’t, of course. Dennis Rader, a bespectacled, balding 59-year-old compliance officer at the time of his arrest, would later to confess to killing 10 victims and share the secret, deviant behavior he’d kept hidden from his wife and two kids for years, how he had a predilection for bondage and sadism, a desire to physically control women he found attractive. But to Rawson, he was the man who took her and older brother Brian Rader on weeklong hiking trips and walked her down the aisle at her 2003 wedding to Darian Rawson, a graphic designer she met while studying at Kansas State. “You don’t want to believe it’s true,” the 40-year-old said in yesterday’s special, her first television interview. “And you know…the father you know is not capable of any of this.”

Rader knew early that there was something off about the way his mind worked. As a child in the small town of Pittsburg, Kan., he enjoyed hanging or strangling farm cats, became excited at the sight of chickens waiting for slaughter and imagined himself torturing woman in abandoned silos. His issues crystalized for him one day when his mom got her ring caught in the spring of a couch. As she sat there pleading with her young son to get help, he realized he was excited by the idea of seeing a woman helpless and trapped.

“When I was in grade school, I sort of had some problems,” he explained in a 2005 audio interview with KAKE TV reporter Larry Hatteberg uncovered for the two-hour Snapped special Oxygen aired last September. “Sexual, sexual fantasies. Probably more than normal. All males probably go through some kind of, uh, sexual fantasy. Mine was just probably a bit weirder than other people.”

During his teen years, he would bind his hands and ankles with rope or cover his head with a bag to restrict his breathing like he would one day do this victims. Paging through magazines, he’d cut out the photos of women he found particularly arousing, drawing ropes and gags on them, imagining ways he could physically control them.

Still, after high school, he set about adulting much like any average midwesterner. Following a four-year stint in the Air Force as a mechanic, he found work as an electrician at Cessna Aircraft Company in Wichita and when he met Paula Dietz, a bookkeeper for Snacks convenience store, through church, he proposed just a handful of dates in. They wed in May 1971.

Two-and-a-half-years later, after he was laid off from his electrician gig, he’d commit his first set of murders, or “projects” as he’d come to think of his victims.

Having cut the phone lines to the Otero’s residence, he forced his way in using a gun. Then he set about suffocating the foursome by using a plastic bag. “I tried to make Mr. Otero as comfortable as I could,” he would later share during a court hearing. “Apparently he had a cracked rip from a car accident. So I had him put a pillow down for his head.”

While his method worked for Joseph and his son, Rader’s inexperienced caused issues. “I had never strangled anyone before,” he explained. “So I really didn’t know how much pressure you had to put on a person or how long it would take.”

AP Photo/Travis Heying, Pool

He ended up strangling Julie with a rope and taking her young daughter downstairs where he hung her from a drain pipe. Their oldest child, 15-year-old Charlie Otero, would discover his parents’ lifeless bodies when he returned home from school with his other siblings.

“I went to the back door of the kitchen entrance and opened it up and walked inside, and I looked at the stove. And my mom’s purse was on the stove, flipped up and disheveled, stuff thrown everywhere. That wasn’t typical of my mother at all. She was a very tidy person and the kitchen never looked like that. So I yelled out. I said, ‘Is anybody home?'” he recalled in the special. “I ran down the hall, went in their bedroom and saw my mother on the bed, my father on the floor, and my heart just got ripped out of my chest. My life changed instantly. When I looked at my mother, she was tied up. It didn’t even look like my mother. My dad, he had a belt wrapped around his neck.”

Three months later, Rader struck again, taking the life of 21-year-old Kathryn Bright, who lived near the Wichita State University campus—as her 19-year-old brother Kevin Bright attempted to flee, he shot him twice in the head, nearly killing him as well.

Soon, though, it wasn’t enough to simply commit violence. He wanted credit for it. Thus began his one-man publicity campaign meant to advertise his wrongdoings and create his legacy as an evil-doer, beginning with a call to the Wichita Eagle where he claimed responsibility for killing the Oteros and pronounced himself BTK. If they looked inside an engineering book at the Wichita Public Library he shared, they’d find a letter describing the murders in depth and announcing his intentions to kill again. How many people did he have to kill, he’d wonder in a subsequent letter, before he got some national attention for his work?

That winter, he’d enroll at Wichita State to study law enforcement, often using library study sessions as an alibi to hunt for victims, a process he called trolling that could take months or even years.

Travis Heying/The Wichita Eagle via AP, Pool

Once he’d keyed in on a future victim, he’d set about stalking, waiting for his perfect moment. He also started work installing ADT security systems, the same protection families were ordering in the hopes of protecting themselves from BTK.

In late 1974, Paula revealed to him that she was expecting, causing Rader to take an extended break from his dark double life. “The excitement of knowing that your wife is pregnant, how can that not be a sign you are normal or have normal feelings?” he reasoned in Confession of a Serial Killer: The Untold Story of Dennis Rader, the BTK Killer, the book he helped forensic psychologist Dr. Katherine Ramsland pen. “I was so excited, for us and our folks. We were now a family. With a job and a baby, I got busy.”

But by 1977, he’d grown restless. So that March, while on spring break from his studies at WSU and vacation from his job, he decided to kill Shirley Vian, a 24-year-old mother of two, at random. Locking her sons, age 6 and 8, in the bathroom with toys and blankets, he strangled her as her kids cried and screamed behind the door, desperately trying to get out.

That December, he’d confess to 25-year-old Nancy Fox that he had “sexual problems”, then force her to strip down. After handcuffing her, he strangled her with a belt, then pleasured himself over her dead body. The next day he called the police to report the homicide. At the time, his wife Paula was expecting their second child, a daughter they would name Kerri.

Outwardly, Rader presented himself as the quintessential family man. At their three-bedroom ranch in the quiet suburb of Park City, his daughter has shared, she had all the trappings of a normal childhood: an older brother, a dog and the backyard treehouse their father had built for them to play in.

“He was just a dad,” she put it plainly to the Kansas City Star in 2014, her first interview after she discovered her father’s horrifying double life. “He taught us about nature. How to fish. How to go camping. How to garden. He taught me a ton. He took us on good vacations. He was pretty Boy Scouty—no swearing.”

There were flashes of anger “or outbursts that you weren’t expecting,” she shared with 20/20, but “most of the time, [my father] was even-keeled and kind and warm.”

That everyman persona proved to be the perfect cover. Rader would claim his eighth victim, 53-year-old grandmother and widow Marine Hedge, while on a Cub Scout camping trip with his son in April 1985. He later told police, he snuck away to commit the murder, returning by the morning.

“She lived down the street from us,” Rawson writes in her new book, A Serial Killer’s Daughter, recently excerpted by People. “Mrs. Hedge went missing on a stormy night. When I heard the police were searching for her, I felt scared. I was six, and only Mom and I had been home that night.”

This is when Rawson estimates the night terrors began. “When Mom heard me scream, she would try to soothe me back to sleep,” she wrote. “I’d say, ‘There’s a bad man in the house—in my room.’ She would gently reassure me. My dad was across the hall—and he’d never let anyone or anything hurt us.”

The irony seems rich now, but at the time Rawson, much like many little girls, saw her father as her protector. He was the guy who let her stay up late watching scary movies, shared paperback mysteries he knew she would love and joined her on walks with their dog Patches.

But he was also the man who murdered his tenth and final victim, Dolores Davis, in 1991, a 62-year-old grandmother who lived just a few miles from them. He used a cinderblock to break through her sliding glass door, later dumping her body by a bridge.

Looking back with a healthy dollop of hindsight, there were certainly signs of the violence he was capable of. “As early as I can remember, being around Dad was complicated,” Rawson wrote in A Serial Killer’s Daughter. “When his eyes turned dark—stormy like the unsettled sea—it was wise to stay clear. I learned at an early age that if you could get Dad outside, the haunted look in his eyes would fade, and he would just be Dad again.”

And then there was the time he wrapped his hands around 21-year-old Brian’s neck mid-argument. “Dad’s eyes and face were blazing, close to manic,” she shared. “My brother, terrified, turned white. Yelling, Mom and I pushed at Dad and were able to break it up. He threatened us kids before but had never physically hurt us. At the time, we dismissed it. Dad is under a lot of stress. He just lost control.”

AP Photo/Travis Heying, POOL

She never imagine she’d learn what he did when he really flew off the handle.

Ultimately, it was Rader’s cocksure attitude that led to his capture. After reading the Wichita Eagle‘s story about the unsolved Otero murders, he sent the paper a letter from a persona he named Bill Thomas Killman, an obvious alias for BTK. “I’ll never forget that day,” former detective Kelly Otis shared with 20/20. “We opened it up and it was pictures of Vicki Wegerle, who was killed in 1986 in her home.”

Rader had boxes filled with such souvenirs, often scouring his victims’ homes for trophies post-kill and gravitating toward driver’s licenses and lingerie. Some he would stash at church, others he would bury or tape to bridges, but the bulk he kept in his house. “Part of my M.O. was to find and keep the victim’s underwear,” he shared in Confessions of a Serial Killer. “Then in my fantasy, I would relive the day, or start a new fantasy.”

AP Photo/Pool, Bo Rader

Between 2004 and 2005 he sent a series of letters to the Wichita Eagle and KAKE-TV, ABC’s Wichita affiliate. In one, he described the location of a cereal box he had left on a lone county road. “Cereal boxes because serial killer,” Ramsland explained to 20/20. “He thought this is a great joke….He got these dolls dressed them to look like his victims, put them into the boxes with…some of the victims’ items.”

He dropped another cereal box in the bed of Home Depot employee’s pickup truck, including a letter that asked police if they’d be able to trace the origins of a floppy disk if he sent it to them. “Be honest,” he implored, instructing them to put a message with their response in the Wichita Eagle‘s classified ads.

“So law enforcement put an ad in the paper that said, ‘Rex, it’ll be OK,'” revealed Wichita Police detective Tim Relph. “Eventually the disk arrives, and it is taken directly to a forensics software detective.”

While Rader genuinely believed the police would be truthful, they were able to track the disk’s data to a computer registered at Park City’s Christ Lutheran Church and a user named Dennis. Some quick Googling led them to Rader.

The next step was to get their hands on DNA to test against the specimens that had been collected at crime scenes and preserved for decades and a search warrant of his daughter’s medical records led them to a collection of Rawson’s pap smears.

“I had no idea,” Rawson shared with 20/20. “It would’ve been nice if someone had asked me for my DNA. I would’ve willingly given it. I understand why nobody approached me. They needed to catch my dad. They needed to be safe about it. They needed to do it quick….At the time, it felt like an invasion of my privacy.” When the DNA came back a match, said Otis, “we knew we had our guy.”

They called in some 200 officers as backup along with helicopters and an actual tank, apprehending him as he was leaving work to have lunch with his wife. “He was absolutely caught because of his hubris and his obsession with being famous and being known as this serial killer,” Deborah Roberts, who interviewed Rawson for the 20/20 special tells E! News. “It was that ego that led to his capture.”

AP Photo/Jeff Tuttle

As much as he had wanted his work to be recognized, Rader seemed simply unable to accept responsibility after his capture. In court he was asked to recount each murder and spent an hour sharing details with little emotion. “It was hard to stomach,” Davis’ son Jeff Davis told 20/20. “He’s up there in front of all these people, admitting these unspeakable crimes. And he’s giving the judge a lesson in serial killer 101. That’s his arrogance.”

In the 2005 interview, granted because the station was a favorite of his as a child, he blamed something he called “Factor X” for his urge to kill.

“I personally think, and I know it’s not very Christian, but I actually think it’s a demon that’s within me,” he said. “At some point and time, it entered me when I was young. And it basically controlled me.”

He felt some remorse for what he’d done, he shared, or at least would hate to think of something similar happening to his own family, but he also derived quite a bit of satisfaction from his work. “I guess it’s more of an achievement for this object in the hunt,” he explained. “Or sort of more of a high, I guess.”

And he certainly had no intentions of coming down. He thought he’d continue his work, having already selected his next target at the time of capture, “I just played cat and mouse too long with the police and they finally figured it out.”

His wife immediately cut ties after learning the truth. She was granted an emergency divorce shortly before Rader officially confessed to the 10 murders in August 2005, receiving consecutive life sentences that amounted to 175 years in jail without the possibility of parole. But Rawson struggled to find closure. At the advice of a pastor at their church, she wrote her father a letter.

“Dear Dad, No matter what you may have done or not done, you are my father and I love you…” she wrote in her book, recalling that initial note. His response was largely unsatisfying, giving her few answers behind an admission he had “serious problems”, yet she continued to write.

“I had to learn how to grieve a man that was not dead, somebody I loved very much that no one else loved anymore,” she explained to 20/20. “I wasn’t corresponding with BTK. I’m never corresponding with BTK. I’m talking to my father. I’m talking to the man that I lived with for 26 years….I still love my dad today. I love the man that I knew. I don’t know a psychopath….That’s not the man I knew and loved.”

But after his sentencing “I shut down,” she told 20/20. “I was mad. I was done. I wiped my hands of him for two years.” She would reach out again in 2007 to inform him she was pregnant with daughter, Emily, now 10, (she also has a 7-year-old son named Ian), but then went silent for the next five years.

As Christmas approached in 2012, she was driving home from a movie with a friend when she experienced a type of epiphany, forgiveness unexpectedly washing over her, as she detailed in her book. “I was sobbing so hard, I had to pull over. White-hot cleansing light overwhelmed my soul—setting me free. It wasn’t from me—It was from God.”

Bursting into her home, she informed her husband that she’d decided to forgive Rader, quickly scribbling out a six-page letter explaining that she had let the pain go, but she could would never be able to understand what he did or why he did it. That she absolved him for what he’d done to their family, but not all the others he had destroyed.

“There have been massive struggles since forgiving my dad,” she shared in A Serial Killer’s Daughter. “Yet on the days when I’m not wresting with hard, terrible truths, I will tell you: I love my dad—the one I mainly knew. On the good days—I’m as near as I can be to being healed.”