Much like the music he wrote, Freddie Mercury‘s life, brief as it was, is hard to pin down.

Take “Bohemian Rhapsody,” for example. That six-minute track, one of rock music’s all-time best and most-beloved, is an exercise in excess. It’s a ballad, then it’s a melodramatic opera, then it’s a head-banging rocker, then it turns quietly introspective; all tied together by a lyric that expresses a longing for freedom and an admission of guilt. It’s beauty and it’s torment, all at once.

Somehow, whether he knew it or not, it’s the song of Mercury’s life.

The iconic Queen frontman, whose story was brought to life on the big screen by Rami Malek in last year’s Oscar-winning biopic Bohemian Rhapsody, began life not as Freddie Mercury, but as Farrokh Bulsara. Born in Zanzibar, an island off the coast of Tanzania, then a protectorate of Britain, to Parsi parents, followers of the Zorastrian religion whose ancestors came from Persia, on September 5, 1946, Mercury would’ve been 73 today.

Phil Dent/Redferns

Bomi Bulsara, his father, was a high-court cashier for the British government, meaning that he, his wife Jer, Farrokh and their younger daughter Kashmira were able to live in cultural privilege, standing in stark contrast to much of their island home’s population. By the time their son was eight years old, in 1954, he was sent to St. Peter’s Church of England School all the way in Panchgani, India, near his parents’ home city of Bombay, now Mumbai.

By all accounts, Mercury arrived at St. Peter’s as a terribly shy child, self-conscious over the prominent overbite his upper teeth gave him, earning him the nickname “Bucky.” But he soon began to blossom, earning the more affectionate nickname of Freddie from his teachers as he began to develop his own tastes.

“He was quite happy and saw it as an adventure as some of our friends’ children had gone there,” his mother told The Telegraph in 2011. “Right from the start, Freddie was musical. He had it on his mind all the time. He could play any tune. He could hear something and play it straight away.”

Four years into his studies at St. Peter’s, he’d formed his first band with some classmates, known as the Hectics. And as Gita Choksi, a student at a neighboring girls school, recalled in Freddie Mercury: The Definitive Biography, when he hit the stage, he was shy no more. “He was quite the flamboyant performer,” she said, “and he was absolutely in his element onstage.”

“Yes, Freddie was very shy. But he was also ‘a born show-off,’ and his entire personality would transform once he was performing. To give you one example: one evening, as teenagers, we were walking on a beach in Zanzibar. Music was playing and Freddie spontaneously started to do the twist, the popular dance move of the time,” Subash Shah, one of Mercury’s friends, told journalist Anvar Alikhan in 2016. “It was such a mesmerizing performance that the next thing we knew was that a group of conservative local girls, wearing burqas, had formed a circle around Freddie and began to twist with him. That was the power of his showmanship, even back then.

It was at St. Peter’s where questions over Mercury’s sexuality began to form. Another student, Janet Smith, now a teacher at the girls school, remembered him as “an extremely thin, intense boy, who had this habit of calling one ‘darling,’ which I must say seemed a little fey.”

“It simply wasn’t something boys did in those days,” she said in Lesley-Ann Jones‘ Mercury: An Intimate Biography of Freddie Mercury. “ It was accepted that Freddie was homosexual when he was here. Normally it would have been ‘Oh, God, you know, it’s just ghastly.’ But with Freddie somehow it wasn’t. It was OK.”

Mercury returned to Zanzibar in 1963, the same year that British colonial rule ended, leading to a revolution on the island the following year, with poor Africans targeting the wealthier Indian population. As a result, the Bulsara family fled to London, eventually settling in nearby Feltham, Middlesex. Having left Farrokh behind in Mumbai, though still using Bulsara as his last name, Mercury enrolled at Isleworth Polytechnic in West London, studying graphic design, but was soon caught up in the era of Swinging London.

“Most of our family are lawyers or accountants, but Freddie insisted he wasn’t clever enough and wanted to play music and sing,” his mother told The Telegraph in 2012, laughing. “My husband and I thought it was a phase he would grow out of and expected he would soon come back to his senses and return to proper studies. It didn’t happen.”

RB/Redferns

After transferring to Ealing Art College, where he earned his diploma in Art and Graphic Design, he met fellow student Tim Staffell, then the bassist in a band called Smile alongside guitarist Brian May and drummer Roger Taylor. In early 1969, Staffell introduced his new friend to the band. “At that stage, he’s just kind of an enthusiast,” May told Mojo in 1999. “He says, ‘This is really good – it’s great how . . . you’re aware of building up atmospheres and bringing them down. But you’re not dressing right, you’re not addressing the audience properly. There’s always opportunity to connect.'”

As he grew closer to the boys in the band—selling odds and ends at a clothes stall in the bohemian Kensington Market with Taylor, sharing a flat with both Taylor and May—he was in and out of a couple groups of his own, attempting to insert as much influence over them as he could. But when he saw Smile, his ambition became being their lead singer, even taking to yelling at their shows, “If I was your singer, I’d show you how it was done.”

By early 1970, Staffell had chosen to leave the group and in April, May and Taylor decided to form a new band with Mercury. Right away, he began to exert his influence on the group, which came to include bassist John Deacon, pushing them to dress more theatrically and insisting they name the band Queen. “It was a strong name, very universal and very immediate,” he would explain years later, according to Rolling Stone. “It had a lot of visual potential and was open to all sorts of interpretations, but that was just one facet of it.”

It was around this time that he’d left his surname behind for good, officially becoming Freddie Mercury. “I think changing his name was part of him assuming this different skin,” May said in the 2000 documentary, Freddie Mercury: The Untold Story. “I think it helped him to be this person that he wanted to be. The Bulsara person was still there, but for the public he was going to be this different character, this god.”

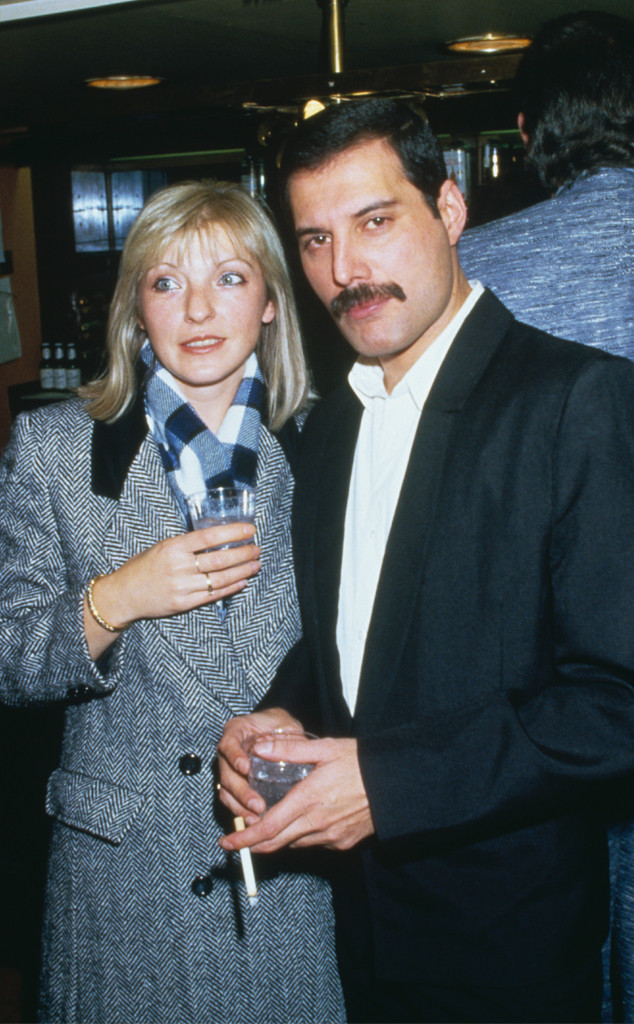

As Queen was coming together, Mercury was also in the beginning stages of what would come to be one of his life’s most defining relationships.

In 1969, thanks to May, he was introduced to Mary Austin, an employee at hip West London boutique Biba. As May explained in the 2000 doc, he and Mercury would frequent the shop to get a look at the “gorgeous” employees. After May took Austin out on a date, Mercury took a liking to her, routinely visiting the store over five months before finally asking her out.

Initially, she found the “wild-looking artistic musician” intimidating, albeit fascinating. “He was like no one I had met before. He was very confident – something I have never been,” Austin, who rarely speaks about Mercury with the press, told the Daily Mail in 2013. “We grew together. I liked him and it went on from there.”

They quickly moved in together, and as Queen took off, life changed for the girl from the working-class family with two deaf parents. In December of 1973, five months after the release of the band’s self-titled debut album, Mercury proposed to Austin after years of avoiding talk of their future.

Dave Hogan/Getty Images

“When I was 23, he gave me a big box on Christmas Day. Inside was another box, then another and so it went on. It was like one of his playful games. Eventually, I found a lovely jade ring inside the last small box,” Austin told Daily Mail. “I looked at it and was speechless. I remember thinking, ‘I don’t understand what’s going on.’ It wasn’t what I’d expected at all. So I asked him, ‘Which hand should I put this on?’ And he said, ‘Ring finger, left hand.’ And then he said, ‘Because, will you marry me?’ I was shocked. It just so wasn’t what I was expecting. I just whispered, ‘Yes. I will.'”

To those in Mercury’s inner circle, the relationship never made much sense—and not just because she was a woman. “She was the opposite of Freddie,” Jones, who also toured with the band throughout the ’80s, told Page Six. “She never really said very much.” But Mercury’s life was full of little compartmentalized selves, and Austin appealed to the homebody in him.

But as he became an international star, touring the globe and exploring a side of himself that he couldn’t quite verbalize just yet, he never really seemed keen on following the engagement up with a wedding. “Sometime later, I spotted a wonderful antique wedding dress in a small shop. And as Freddie hadn’t said anything more about marrying, the only way that I could test the water was to say, ‘Is it time I bought the dress?’ But he said no. He had gone off the idea and it never happened,” Austin recalled. “I was disappointed but I had a feeling it wasn’t going to happen. Things were getting very complicated and the atmosphere between us was changing a lot. I knew the writing was on the wall, but what writing? I wasn’t absolutely sure.”

By December 1976, three years after proposing and five albums deep into Queen’s career, Austin had noticed that Mercury was staying out alter and alter and believed he might be having an affair with another woman. And then he sat her down and told her he had something important to say.

“I’ll never forget that moment. Being a bit naive, it had taken me a while to realize the truth. Afterwards he felt good about having finally told me he was bisexual,” she said. “Although I do remember saying to him at the time, ‘No Freddie, I don’t think you are bisexual. I think you are gay.'”

They hugged, her told her that, no matter what, he always wanted her to be a part of his life, and they carried on an unconventional routine for a time, where Mercury would be flanked on either side at dinner parties by Austin and boyfriend of the moment.

“I always thought, how weird is that?” Jones said of the arrangement. “Go have a life. Don’t stay glued to the hip to this person who… isn’t going to be able to offer you a conventional relationship. After they separated, she even suggested to Freddie that they have a child together. Freddie told her that he would rather have another cat.”

Larry Marano/Getty Images

Despite the end of their relationship, they remained a constant presence in each other’s lives. Mercury bought her an apartment nearby the house he moved into and she remained on the payroll as something of his right-hand man. Though she had two children with with painter Piers Cameron and later married and divorced businessman Nick Holford—and despite Mercury’s many dalliances and relationships after Austin—he considered her his “common-law wife.”

“All my lovers asked me why they couldn’t replace Mary, but it’s simply impossible,” he famously said in a 1985 interview. “The only friend I’ve got is Mary, and I don’t want anybody else. To me, she was my common-law wife. To me, it was a marriage. We believe in each other, that’s enough for me.”

In the late ’70s and through much of the ’80s, the band came to consider Munich their second home, and the city’s active and diverse sex culture became a playground for Mercury. He’d begun a sexual relationship with his manager Paul Prenter, which would soon sour spectacularly, began throwing debauched and drug-fueled sex parties, had a romantic relationship with German soft-porn actress Barbara Valentin and could hardly be bothered to waste his time in the studio. “He’d want to do his bit and get out,” May would later recall.

As Mercury was devolving further into a sex-soaked lifestyle, Prenter began to be the wedge that came between Mercury and the rest of the band. In 1982, after the album Hot Space was released to poor reception, May and Taylor lay the blame on Prenter and his influence over Mercury. (Though, to be fair, there were cracks in the quartet’s bond already, cracks that didn’t begin with Prenter.) He was regarded by several band associates as a self-serving parasite, something that would prove true a few years down the road.

As we head further into the ’80s, Mercury’s story becomes entangled with the AIDS crisis that was engulfing the gay community. How exactly he contracted the disease that ultimately took his life remains a mystery, with varying accounts floating around. However, what’s not hard to see is that it was his free-wheeling attitudes towards unprotected sex just couldn’t have come at the wrong time.

BBC DJ Paul Gambaccini recalled running into the singer one night in 1984 at a London nightclub, where he asked Mercury if AIDS has changed his attitude toward sex. His response? “Darling, my attitude is ‘f–k it.’ I’m doing everything with everybody,” according to Rolling Stone. It left the DJ worried. “I had that literal sinking feeling,” he said. “I’d seen enough in New York to know that Freddie was going to die.'”

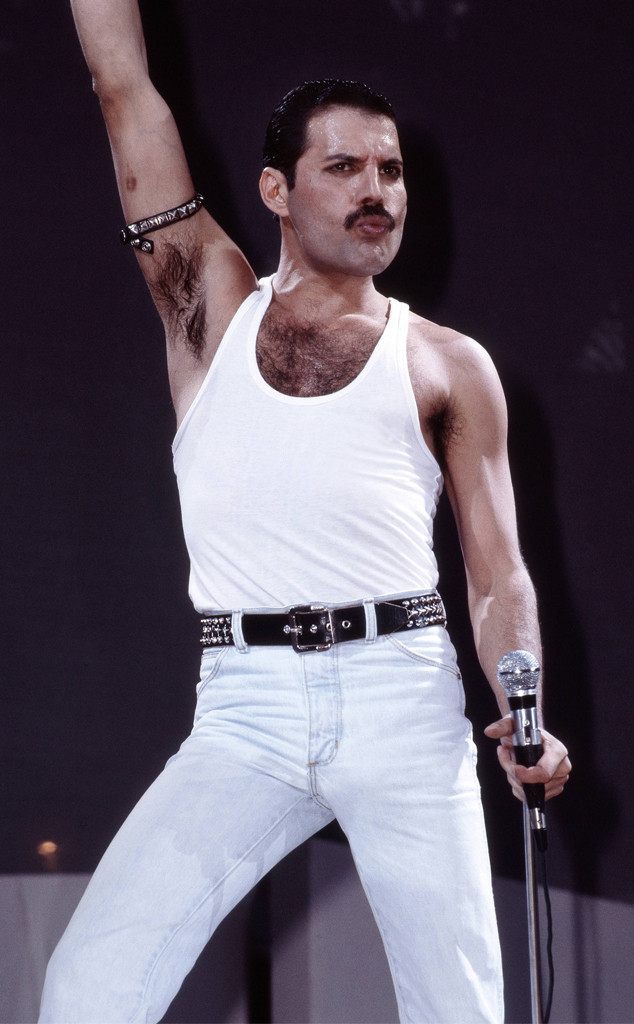

In late 1985, after the band gave a career-revitalizing performance at that summer’s Live Aid London concert, he got tested and the results were negative. He then abandoned the club scene, and Prenter soon thereafter, and settled into a quieter life at his mansion in Kensington. “I lived for sex,” he would later say. “I was extremely promiscuous, but AIDS changed my life.”

After Prenter was fired and removed from Mercury’s life, he retaliated with a 1987 tell-all interview with British tabloid The Sun, in which he outed Mercury and revealed his relationship with hairdresser Jim Hutton, whom he’d been involved with since 1985, as well as his earlier blood test. This was also the year that Mercury got himself re-tested—with very different, damning results.

Only, he didn’t seem to want to know. After taking the test, he avoided his doctor’s many attempts to reach him, and the office was forced to contact Austin and share the grim news with her. “I felt my heart fall,” she would later say. Though the press was circling Mercury, looking for answers, he and the band closed ranks, choosing to focus instead on recording as much as possible in whatever time he had left.

“He decided to just invite us all over to the house for a meeting,” Taylor said of Mercury following the completion of their 13th album in early 1989. He told his bandmates, “You probably realize what my problem is. Well, that’s it and I don’t want it to make a difference. I don’t want it to be known. I don’t want to talk about it. I just want to get on and work until I fucking well drop. I’d like you to support me in this.”

Naturally, May, Taylor and Deacon were devastated, as the guitarist later admitted to. “We all went off and got quietly sick somewhere, and that was the only conversation directly we had about it,” he said.

Dave Hogan/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

By September 1991, after the release of Innuendo, their 14th album, Mercury was done with the race to record and retired to his home. He kept his family at arms length as he began to succumb to his illness, never explicitly telling them what was going on. “He protected us by never discussing these matters,” his mother told The Telegraph. “It is quite different now, but back then it would have been very hard for him to tell us and we respected his feelings.”

He had stopped taking his medication, had several bouts of blindness, and was turning away most visitors, though Austin and Hutton remained by his side until the very end. He also continued to deny any and all reports that he had AIDS until November 23, 1991, when he issued a statement admitting the truth. “Following enormous conjecture in the press, I wish to confirm that I have been tested HIV-positive and have AIDS. I felt it correct to keep this information private in order to protect the privacy of those around me,” the statement read. “However, the time has now come for my friends and fans around the world to know the truth, and I hope everyone will join with me, my doctors and all those worldwide in the fight against this terrible disease.”

He died the next day at the far-too-young age of 45.

His funeral took place within days of his passing. Aretha Franklin performed at the Zoroastrian ceremony. And choosing to remain a mystery even in death, his body was cremated, with Austin, whom Mercury left the bulk of his fortune and his mansion, charged with placing his ashes in a location she’s never disclosed. “One morning, I just sneaked out of the house with the urn. It had to be like a normal day so the staff wouldn’t suspect anything – because staff gossip,” she told Daily Mail. “They just cannot resist it. But nobody will ever know where he is buried because that was his wish.”

In the years since his death, and especially since the biopic went into production, there’s been much debate over what Mercury’s legacy might be. Is he a queer icon first? Or a musical legend? And must those be mutually exclusive?

Mercury was once asked what “Bohemian Rhapsody” meant. “F–k them, darling,” he said. “I’ll say no more than what any decent poet would tell you if you dared ask him to analyze his work: ‘If you see it, dear, then it’s there.'”

Little did we know that the poet was talking about something bigger than his work. Little did we know he was talking about himself.

(This story was originally published on November 2, 2018 at 3 a.m. PT.)