CBS via Getty Images

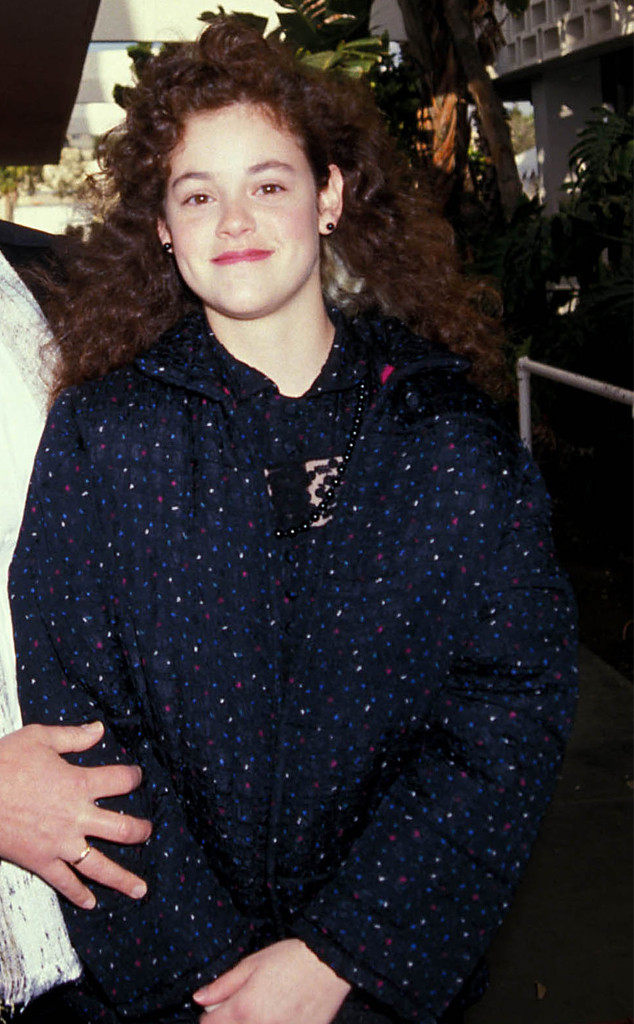

Rebecca Schaeffer thought it was sweet that a fan was sending her stuffed animals and other little gifts at the studio lot where her sitcom My Sister Sam was filmed.

The CBS show, on which she played a spunky teen who goes to live with her photographer sister in San Francisco, was her big break after just a few acting jobs, and she had quickly become a favorite of the Seventeen-reading set. (Not to mention, the fresh-faced brunette had been on the magazine’s March 1987 cover.)

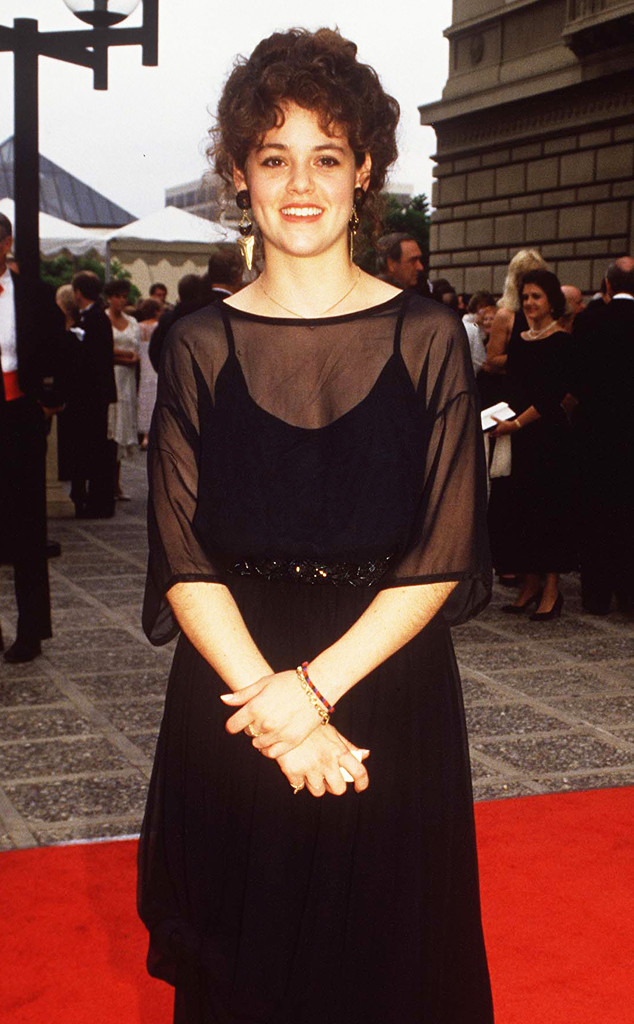

My Sister Sam ended in 1988 after two seasons, but the work kept coming. Schaeffer co-starred in the racy big-screen farce Scenes From the Class Struggle in Beverly Hills, which hit theaters in June 1989. She had wrapped the TV movie Voyage of Terror: The Achille Lauro Affair, about the real-life 1985 hijacking of a cruise liner, with screen legends Eva Marie Saint and Burt Lancaster. Dyan Cannon had just directed her in a movie, The End of Innocence, in which Schaeffer played a younger version of Cannon’s character.

She was even said to be in the running for the lead in an upcoming romantic comedy called Pretty Woman.

And on the morning of July 18, 1989, the 21-year-old from Oregon was waiting for a delivery that, if all went well, could change her life.

Schaeffer was scheduled to audition later that day for the then very coveted role of Michael Corleone’s daughter, Mary, in The Godfather Part III in front of Francis Ford Coppola, and she was expecting the script to be dropped off at her West Hollywood apartment any minute.

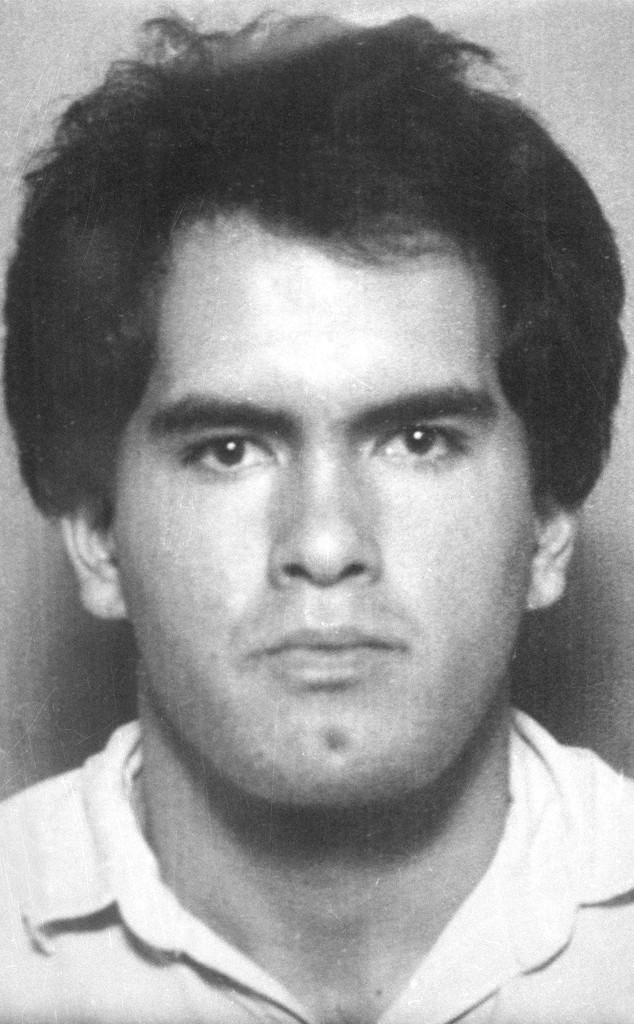

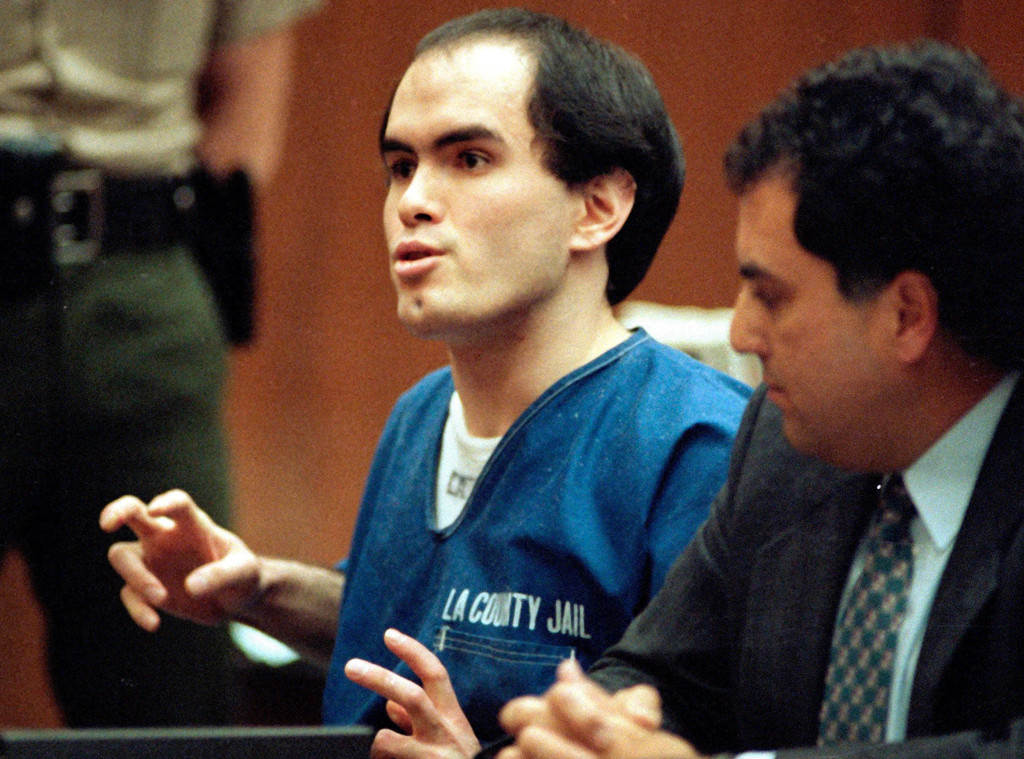

When the bell rang at 10:15 a.m., Schaeffer went to answer the door and was fatally shot by 19-year-old Robert John Bardo. He had been obsessed with the actress for three years and had paid a private investigator $300 to find out where she lived. The P.I. got her address from DMV records. Bardo got his older brother, Edward, to buy him a gun, his own attempt unsuccessful after he told the gun store owner about his history of mental illness.

Edward had told Robert that he could only use the gun when they were together, for target shooting. He bought a .357 Magnum.

“Why?…Why?” was the only thing Schaeffer said after he shot her, according to what Bardo later told a psychiatrist in a jailhouse interview.

Bardo was a freshman in high school when he first saw Schaeffer in a commercial for My Sister Sam in the summer of 1986. He felt that they were kindred spirits, both shy and genuine, and he started sending her tokens of his ultimately deranged affection. He also wrote her letters—and when she replied to one of them, he took that as his cue to travel from Tuscon, Ariz., to Los Angeles to see her.

He went to the studio and brought flowers and a teddy bear, but never made it through security and he eventually went back home.

“I thought he was just lovesick, which I think he was,” Jack Egger, who was chief of security at The Burbank Studios, later told the LA Times. “He was terribly insistent on being let in. ‘Rebecca Schaeffer’ was every other word. ‘I gotta see her. I love her. If I could just see her for a minute.'”

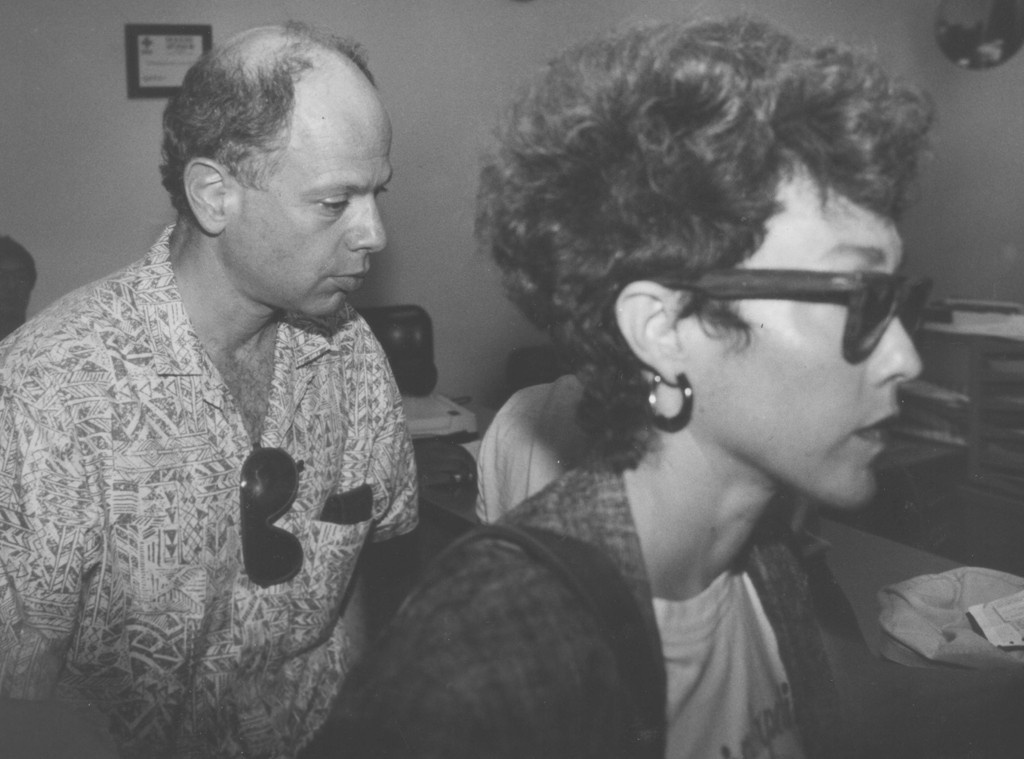

Judy Crown, a veteran hair stylist who worked on My Sister Sam, described Schaeffer as “very beautiful, very sweet, a little bit naive” in an interview for the Television Academy Foundation. Crown recalled telling her, when letters and gifts would arrive on set, “‘Rebecca, don’t respond. Just don’t respond. I don’t have a good feeling about this, don’t respond. People sometimes are crazy, and I think you should just ignore it.'”

Bardo’s opinion of Schaeffer changed, however, after he watched her in a love scene in Scenes From the Class Struggle. He apparently felt betrayed. With his gun and hollow-point bullets in tow, he boarded a bus to L.A.

Schaeffer had no idea that the writer of some of the sweet letters she received had snapped. By all accounts, she was also interminably kind and trusting—not to mention she was waiting for that script—so perhaps that’s the simple reason as to why she was inclined to open the door that day for a stranger—twice. (Moreover, the intercom in her apartment that she could have used to talk to someone outside wasn’t working.)

When Schaeffer first came to the front door of her building, Bardo showed her the letter she had sent him and an autographed photo. He told her he was her biggest fan. She politely told him she had an interview to get ready for. “Please take care,” Bardo later remembered her telling him, and she shook his hand.

AP Photo

After eating at a nearby diner, he returned. He claimed he had forgotten to give her another letter and a CD he had brought for her.

“She said: ‘You came to my door again,'” Bardo said in the jailhouse interview, parts of which were played in court during his trial. “It was like I was bothering her again. ‘Hurry up, I don’t have much time.’

“I thought that was a very callous thing to say to a fan.”

He then told her, “I forgot to give you something,” and shot her with the gun he had brought from Arizona with him in a shopping bag. Schaeffer was pronounced dead at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, less than a mile away.

Shortly after noon, Tom Noonan, a friend of Rebecca’s, left a message for her mother, Danna Schaeffer, a writer and instructor at Portland Community College, in Oregon. About 10 minutes later, taking a break from the play she was writing, she called back.

“I still remember how sunny my voice sounded when he picked up the phone,” she recalled to Entertainment Weekly in 2017. “Then he said, and these words are inscribed in my brain, ‘Mrs. Schaeffer, I have terrible news. This morning Rebecca was shot and killed.'” Danna called the hospital, but they wouldn’t confirm over the phone anything other than that “a woman had been admitted and had died.”

“At that point I kind of knew,” she said. “Then the detective called. And it was all over.”

Two years later, Danna had saved the phone bill that showed the exact time she got the news: July 18, 1989, 12:15 p.m.

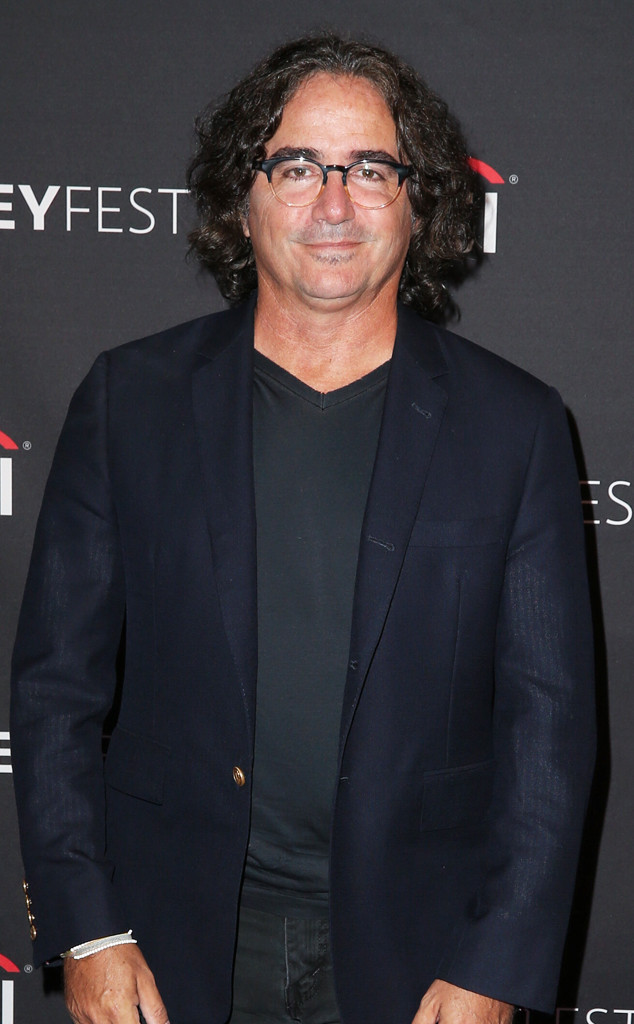

While Schaeffer’s death was a devastating personal loss for her parents, friends and other loved ones, including her boyfriend at the time, director Brad Silberling, the circumstances of the killing also jolted, first, the Hollywood community and then the entire state of California.

Unhealthy obsessions with famous people remain, disturbingly, all too common, with everyone from Taylor Swift and Keanu Reeves to Kendall Jenner and Sandra Bullock having been targeted by overzealous admirers, some of whom have ended up being arrested for trespassing, burglary and other crimes that fit into a pattern of harassment.

While her death wasn’t the only impetus for action, it wasn’t until after Schaeffer’s murder that stalking in and of itself was even classified as a crime.

In 1990, California became the first state to pass an anti-stalking law—in addition to Schaeffer, four women had been killed in Orange County the previous year despite having restraining orders in place against men who had been harassing them—and eventually the rest of the country followed suit.

The Screen Actors Guild also got involved in lobbying the state to strengthen privacy protections, and the state subsequently restricted the accessibility of personal information, such as a home address, from the DMV. (According to a state assemblyman, the California Department of Motor Vehicles received 16 million address inquiries in 1988.) Congress passed the Driver’s Privacy Protection Act in 1994, which required all states to do the same.

CBS Photo Archive/Getty Images

“We weren’t aware of the ripples going out right after Rebecca died,” Silberling told EW in 2017. “But it was an earthquake.” Brad Pitt, still a relative unknown then, lived down the street from where she was killed and he later told Silberling, as the director relayed, “‘It’s no consolation, but the impact of her loss and the sense of awareness and safety for younger actors was huge.'”

Gun control also became a hot topic in the wake of Schaeffer’s death, and the My Sister Sam cast and crew reunited for a PSA about gun violence.

“It wasn’t hard to get it moving at all,” Pam Dawber, who played Schaeffer’s sister on the show, told a Tribune Media reporter in October 1989, “though what is going to be hard is to get the networks to air it. Gun control is fairly controversial, though all we’re saying to people is to prevent handgun violence. Now, how can you argue with that?”

We’ve all since learned the answer to what Dawber probably thought was a rhetorical question.

“We were all out of our minds with grief,” the Mork and Mindy star remembered in a recent interview on ABC News’ 20/20. “It like, this is so horrible. We had a memorial for Rebecca at the studio where we all came together, [thinking] we’ve got to do something to make some sense, to make it so this can’t happen again.”

Larry Davis / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

Rebecca’s parents also threw themselves into the fight for stricter gun laws, imploring lawmakers to tighten restrictions on who could get their hands on a firearm, a battle that’s uncannily similar to the one still being waged today. Danna helped launch the lobbying group Oregonians Against Gun Violence in 1990 and went to Washington, D.C., to help lobby for the passage of the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act.

“We face death every morning,” Benson Schaeffer, Rebecca’s dad, told the Los Angeles Times in October 1991. “Sometimes you’re overcome with despair. You never cease missing the person. The gun issue lets us focus our anger.” (The Brady Bill was eventually enacted in 1993.)

Their main goals didn’t sound particularly extreme. They wanted for all gun sales to have built-in waiting periods, and to have guns only be sold by licensed dealers. “There’s so little we can do about Rebecca’s death,” Benson, a child psychologist, said. “We feel good about doing this. It’s the only public way to say that what happened to Rebecca isn’t all right.”

And in addition to the greater implications of this tragedy, there was, of course, the spectacle of it all: A 21-year-old celebrity, killed by a stalker, at her home, in broad daylight. Terrifying and endlessly compelling.

A portrait immediately emerged of a victim who wasn’t just poised to be a major star, but a person who touched everyone who knew her with her sweet, generous spirit—a portrait that has endured to this day.

Globe Photos/ZUMAPRESS.com

“She didn’t have an enemy in the world,” her agent, Jonathan Howard, told the Los Angeles Times hours after the murder. “She was one of the nicest people I’ve ever known—sincere, honest and kind. She was a very successful young actress, on the ascent, getting job after job. I can’t believe this has happened.”

Twenty years later, the shock was still palpable. Howard told 20/20 in April, “I remember the last time I spoke to Rebecca. It was about The Godfather III audition…How important it was, how excited she was, and you don’t think whenever you talk to somebody that it’s going to be the last time.”

According to her mom, Schaeffer had entertained the idea of becoming a rabbi before moving from Oregon to New York to pursue modeling and acting at 16 and attend Professional Children’s School in Manhattan.

“From my standpoint, it seemed very natural,” Schaeffer later told a Portland newspaper. “But I know my parents went through hell.”

“She was very serious about what she did,” Douglas Ashe, who worked with Schaeffer early in her career at Prestige Models, told People in the days after she died. “We had her room with six other models, and she was always this good kid who never lost her friends or her perspective.”

Donald Sanders/Globe Photos/ZUMAPRESS.com

She also briefly modeled in Japan before making her TV debut in 1985 on the soap opera One Life to Live. Her first movie role was a bit part in Woody Allen‘s Radio Days.

“She was extremely curious and spirited,” Sean Six, an actor who dated Schaeffer in Portland, also told the magazine. “We’d travel, go to parks, have picnics. She liked to horseback ride or just spend time on a mountaintop. She was the only actor I’ve ever known who managed to become successful and remain unjaded.” Overall, “she lived a very quiet life. She was sensitive, kind of a loner.”

Indeed, there were no recollections—then or later, when those sorts of memories tend to start creeping back into the narrative—of Schaeffer being into the typical Hollywood party scene.

“Rebecca liked to stay home and read and play with her cat,” Sue Cameron, a former agent of hers, told E! in 1996 for what was the first-ever episode of E! True Hollywood Story, a deep dive into Schaeffer’s life and death. “She liked classical music. She liked going to the Hollywood Bowl. She was very healthy, so she would work out, she would go for walks. She never went to Hollywood parties.”

Globe Photos/ZUMAPRESS.com

My Sister Sam co-star Jenny O’Hara remembered Rebecca as a regular teen who used to talk to her and Pam Dawber about men and dating, and ask for advice about this or that, yet at the same time she conducted herself in public “with total self-assurance.”

“She was so natural, she was herself,” O’Hara told E!. “There was nothing phony about her, there was nothing put on about her. She was amazing.” And trustworthy. Rebecca was her daughter Sophie’s first babysitter. “And I thought,” O’Hara added, “that she was going to be a remarkable mother.”

CBS Photo Archive/Getty Images

Schaeffer lived with Dawber and her husband Mark Harmon for a few months when she first got to L.A. after getting My Sister Sam.

“We just kind of fell into this sisterly thing,” Dawber told 20/20. “‘Cause I’d had a sister. My sister passed away when she was 22 and I was 25. And so having another young girl in the house was something I was very comfortable with. It was good for us.” The veteran actress was happy to see Rebecca’s career taking off.

“I was thrilled that she was getting to really, really enjoy…a big show biz life,” Dawber said.

Eventually Schaeffer moved out, first to an apartment in the hills above the Sunset Strip, but she worried about being too isolated up there; so, she left for the place on Sweetzer.

Dawber, who had had her own experience with a stalker, recalled, “The one thing we did say to her, though: ‘You never put your real name on your mailbox, Rebecca.’ … And she didn’t listen to that.” Dawber said she always had her business manager’s address on her driver’s license, too, “so that you can’t be found.”

Schaeffer wasn’t wildly famous yet, but her fate ensured that she ended up frozen in time as a bright young talent who was on the verge of movie stardom.

“She came in and I was just knocked over by her presence,” Dyan Cannon recalled to E!. “She was gentle and she was a tiger. She was curious but contented. She was satisfied. That’s a very unusual quality to attribute to a 20-year-old girl.”

Globe Photos/ZUMAPRESS.com

All that extinguished potential, plus the fact that she was a gorgeous young actress, also helped usher in our current habit of paying rapt attention to certain murder trials. Magazines and tabloid news shows like Hard Copy and 48 Hours, both pretty new at the time, couldn’t get enough of the photogenic victim who surely would have been a huge star and a household name for all the right reasons had she not been murdered in cold blood.

“When I found out how Rebecca was murdered…I was staggered because I don’t think at that time we thought about stalking so much,” Cannon said on 20/20 in April. “‘This guy followed her? This guy went to her condo and she opened the door and he shot her and killed her and she’s dead?’…In that time was unthinkable.”

Witnesses later recalled seeing Robert John Bardo on Rebecca’s street, showing passersby her photo and asking if they knew her and where she lived. When he got to her building, he asked a cabdriver waiting at the curb if it was a house or an apartment complex.

Not much later, neighbors heard a shot and screams. Bardo ran off up the street.

“She was lying on the ground…wearing nothing but a little black bathrobe,” Kenneth Newell, who lived in the building next door and ran outside when he heard the shot, told the Los Angeles Times. “Her eyes were open, staring. It looked to me as though she was already dead.”

“We can assume she may have known him, or maybe she was just a trusting person,” LAPD Detective Dan Andrews told reporters that day, speculating as to why Rebecca had opened the door. “We have no record of her ever having called for assistance or being a victim of anything, or being harassed.”

Security at the studio later confirmed that none of the letters sent to Schaeffer on the lot sounded menacing or threatening. Ordinary fan mail, they thought.

“I can only assume that it was somebody who didn’t know her but was obsessed with her,” Paul Bartel, who had just directed Schaeffer in Scenes From the Class Struggle, told People shortly after the murder. “I can’t imagine that anybody who really knew her would do this. She was so mature and intuitive that she would have made sure this couldn’t happen.”

Rick Meyer / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

The following day, Tuscon police received a report of a man disrupting traffic at a major intersection. Bardo, who had been running near a freeway yelling that he killed Rebecca Schaeffer, was arrested and the officers, after finding a photo of Rebecca in his pocket, immediately contacted authorities in Los Angeles. Police there had already received a tip from a woman in Tennessee who said Bardo had been obsessed with Schaeffer. Tuscon police faxed Bardo’s picture over and neighbors identified him as the man they’d seen asking about Rebecca.

The woman turned out to be his sister, and he had written to her in Knoxville before leaving again for L.A., “I have an obsession with the unattainable and I have to eliminate (something) that I cannot attain.”

Before he tracked down Rebecca, he had other problems. He once went to Maine looking for Samantha Smith, a young peace activist who made headlines when she corresponded with Soviet leader Yuri Andropov and traveled with her family to Moscow as his guest. After that, Bardo was put in foster care back in Arizona, but ran away, then ended up in a psychiatric hospital. In 1985 he was discharged and placed in another foster home, which he also ran away from. He worked for awhile as a janitor at a Jack-in-the-Box.

Samantha Smith died in a plane crash in 1985 when she was 13, after which Bardo turned his attention to pop star Debbie Gibson. He went to New York to try to meet her (he did not), and while he was there he visited the spot where Mark David Chapman killed John Lennon in 1980. Though he didn’t stop to read it, as Chapman did, Bardo also had a paperback copy of The Catcher in the Rye on him when he shot Schaeffer.

He got the idea to hire a private investigator from reading a magazine article about Arthur Richard Jackson, who was in prison for stabbing actress Theresa Saldana outside her home in 1982 after tracking her down with the help of a P.I. A native of Scotland, Jackson was in the country illegally (he had previously been deported in 1961 and again in 1966) and had attempted to, but wasn’t able to, buy a gun because he didn’t have a U.S. driver’s license. A Sparkletts water delivery man came upon the attack in progress and wrestled with Jackson, allowing Saldana to get away.

Jackson was convicted of attempted murder and inflicting great bodily injury and sentenced to the maximum prison sentence of 12 years. The maximum penalty was later extended to life in prison, but that didn’t retroactively apply to Jackson. He was granted parole in 1989 but was never released; instead, he ended up being sentenced to almost six more years for sending Saldana death threats. In 1996, a day before he was due to be released on parole, Jackson was extradited to England to stand trial for killing a man during a 1966 bank robbery. Authorities said he confessed to the 30-year-old killing while in prison in California.

When he was first up for parole, Saldana, who was understandably against his release, told the LA Times, “My life is in jeopardy. That is what motivates me…I’m not saying to kill this person. I’m not saying that, and I’m not saying that the reason for further detainment is punishment, not at all. I believe that we have an obligation to protect the public’s safety.”

Anacleto Rapping / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

Bardo said in his jailhouse interview that “there was something very special” about Rebecca. “I just couldn’t let go of her.”

A tough young prosecutor named Marcia Clark caught the case, and early on she agreed not to seek the death penalty when Bardo waived his right to a jury trial.

The absence of a jury didn’t lessen the morbid fascination with the proceedings one bit.

“The Bardo trial became a trial run, so to speak, for the synthesis of justice and celebrity, and foreshadowed what was to come with later high-profile trials of music producer Phil Spector and actor Robert Blake,” NBC 4’s Patrick Healy, who covered the trial, said on Today earlier this month.

Kevork Djansezian/AP/Shutterstock

Remembering the cold dose of reality it served up to not just the famous, but to everyone else, too, Healy said, “It hit home to everyone who drives a car that the person you inadvertently cut off and upset could jot down your license plate number, go to the DMV, get your address, and be waiting with a gun or a knife.

“Nowadays, it is hard to imagine a performer who has co-starred in a network TV series coming to her front door to open the door to a stranger.”

Globe Photos/ZUMAPRESS.com

Dr. Park Elliott Dietz, the psychiatrist who interviewed Bardo at L.A.’s Men’s Central Jail, testified that though he believed Bardo had been schizophrenic since childhood, he didn’t fit the state’s definition of legal insanity.

Adding to the bizarreness of the proceedings, Bardo told Dietz that he was further inspired by the U2 song “Exit,” off their album Joshua Tree, about religious fanaticism turning deadly, which itself was inspired by Norman Mailer‘s The Executioner’s Song, about serial killer Gary Gilmore. Lyrics such as “Hand in the pocket / Finger on the steel / The pistol weighed heavy /His heart he could feel / Was beating, beating / Beating, beating oh my love” do sound especially chilling through that prism.

The song was played in court and it reportedly seemed to invigorate Bardo, who banged his knees like a drum and mouthed the words. He otherwise mainly sat there not moving, looking downcast.

After that information came out, U2 didn’t perform “Exit” again live until 2017, when they toured playing Joshua Tree cover to cover.

Kevork Djansezian/AP/Shutterstock

Bardo’s attorney, Deputy Public Defender Stephen Galindo, argued that his client was too mentally ill to have planned his crime and was guilty of nothing more than second-degree murder.

“Rebecca Schaeffer is a victim in the true sense of the word,” Galindo said in court. But at the same time, “Robert Bardo is also a victim—a victim of parental neglect and a mental health system which failed to provide the treatment he needed.”

Clark agreed that Bardo certainly wasn’t normal, but he wasn’t insane, either. And Superior Court Judge Dino Fulgoni agreed with the prosecution.

On Oct. 29, 1991, Bardo was convicted of first-degree murder with the special circumstance of lying in wait. That December he was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

He’s currently behind bars at Avenal State Prison in California.

Anacleto Rapping / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

But while the legal chapter of Rebecca’s murder was closed, life didn’t all of a sudden go back to normal for her parents, who were then just faced with the daunting task of both moving on and ensuring that their daughter was never forgotten.

Just last year Danna Schaeffer made her performance debut at the Hollywood Fringe Festival in Mid-Air: Elegy for a Daughter, a one-woman show she wrote about the loss of her only child.

“It ends now with finally arriving at some tentative resolution about accepting that she’s not here,” she told the Los Angeles Daily News.

David Buchan/Variety/Shutterstock

Brad Silberling’s 2002 film Moonlight Mile, about the complicated relationship between the boyfriend of a murdered young woman and her parents, was inspired by his experience briefly living with the Schaeffers in Oregon after Rebecca was killed. Silberling said he didn’t date for two years afterward.

“I wanted to explore this very strange journey that I’d never seen on film,” he told the Jewish Journal in 2002. “Like, how you go through every possible emotion in the aftermath of a death. For example, I’d be sitting with Rebecca’s parents, and we’d just be roaring with laughter, dishing on people who were mouthing [platitudes]. There would be this bizarre, completely inappropriate humor at moments you’d never expect.”

Silberling was 23 and in graduate school at UCLA when he met Schaeffer on a blind date in 1987. “We just sort of fell into each other’s lives,” he said.

CBS Photo Archive/Getty Images

The morning she died, he recalled, he discovered a sweet message she had left on his answering machine. It was the last time he ever heard her voice. A few hours later he was at Cedars, waiting while Schaeffers’ parents identified her body.

Silberling remained close to the Schaeffers and they were at his wedding when he married Amy Brenneman in 1995.

He told The Guardian in 2003 about the process of making Moonlight Mile, “I was exploring how it is that I ended up still able to find hopeful things in life. I have family now and somehow survived the experience. With this film, I was trying to figure out how that became possible.”

“What the world really lost was an angel,” Jonathan Howard, Rebecca’s former agent, said on 20/20. “I lost a friend. … Hollywood lost a rising star, and the world lost an angel.”

Benson Schaeffer remembered the last time he talked to his daughter. She had called a day or two before her big Godfather audition.

“She had been invited to go… on a set,” he said. “[I said] ‘Why don’t you give me a ring afterwards and tell me how it went.’ And she said, ‘Well I’ll do that. I love you.’ And I said, ‘I love you.’ And that was the conversation.”