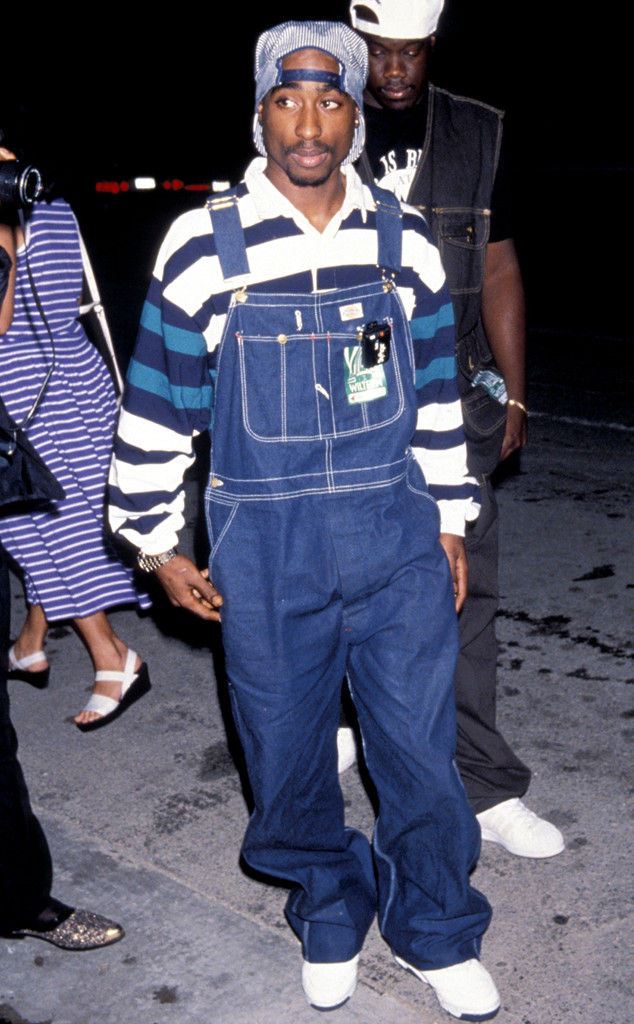

Al Pereira/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

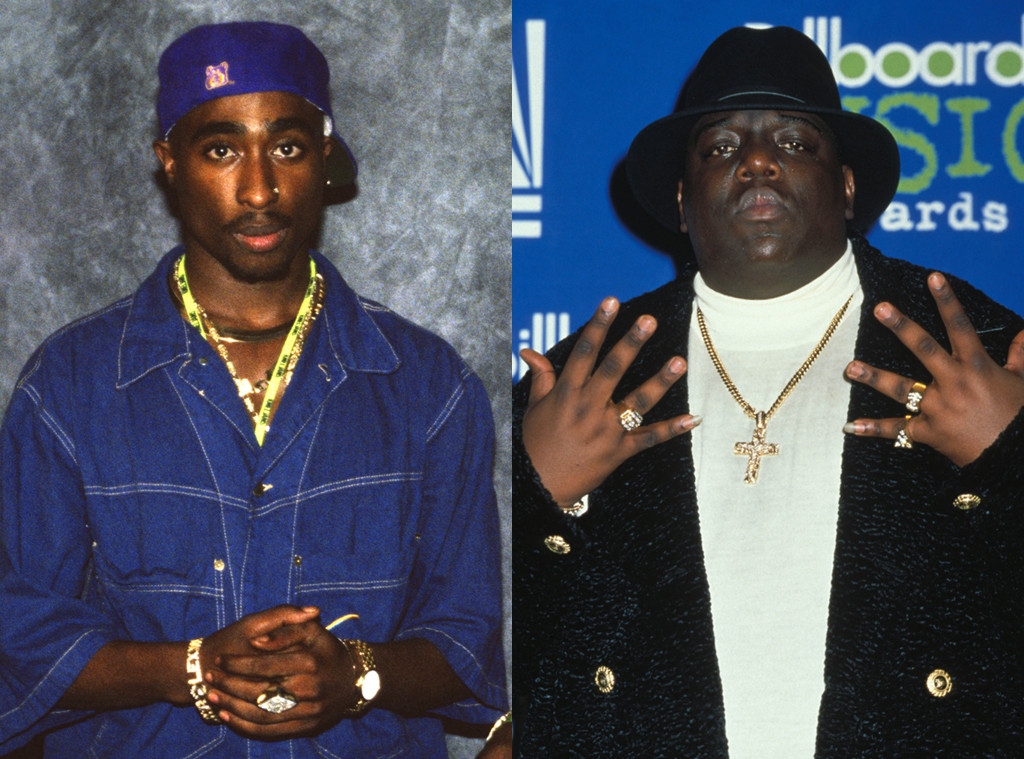

In 1996, Tupac Shakur was the crown prince of West Coast rap.

Traveling the road paved by hip-hop pioneers like Dr. Dre, Ice Cube, Snoop Dogg and Ice-T but also blazing his own way as an inimitably talented but complicated provocateur, the All Eyez on Me artist had emerged as a boldly honest, startlingly prescient voice poised to change the game forever.

Which he did, only he didn’t live to see it.

On Sept. 7, 1996, Shakur, who would have turned 48 today, arrived in Las Vegas to attend a Mike Tyson fight with Death Row Records co-founder Marion “Suge” Knight at the MGM Grand. His bodyguard Frank Alexander had arrived the day before to ensure the trip went as smoothly as possible. Alexander was perturbed to find out that guests were being asked not to bring any guns into Knight’s 662 Club, where they planned to party after the fight. “Big Frank,” as the rapper called him, didn’t like the idea of being without a weapon while protecting Shakur, who attracted a crowd wherever he went.

Tyson, a close friend, entered the ring to Shakur’s “Let’s Get It On,” and knocked Bruce Seldon out in the first round.

As Shakur, Knight and assorted entourage members were leaving the MGM, Knight associate Travon Lane came up to Tupac, whispered something to him, and the rapper took off, with Frank close behind. When the bodyguard caught up, Shakur was exchanging punches with a man named Orlando Anderson, who was linked to the Los Angeles-based South Side Crips gang. (Knight and Death Row were famously associated with the rival Mob Piru Bloods.) Hotel security broke up the fight, and the Death Row crew returned to the Luxor, their preferred place to stay in Vegas.

As if nothing had happened, they got ready for their night out at 662. Frank planned on going with Shakur in Knight’s BMW, but Shakur handed him the keys to his girlfriend Kidada Jones‘ car and instructed Frank to drive his backup group, the Outlawz, to the club.

Ron Galella/WireImage.com

So Suge was behind the wheel of his BMW, with Tupac in the passenger seat. Frank followed behind, and he wouldn’t even stop for gas when the warning light went on, so concentrated he was on his charge.

The group spent about 30 minutes at Knight’s house before the caravan took off for 662. Suge and Tupac were blasting music. Stopped in traffic on Las Vegas Boulevard, aka the Vegas Strip, a bicycle cop approached Knight’s car. Frank observed Knight getting out of the car and opening the trunk for the cop, who sent them on their way.

At the next intersection, shortly after 11 p.m., a white Cadillac pulled up next to Knight’s car. A gun-wielding hand poked out and fired 14 shots into the BMW. (The black 1996 BMW has been fully restored and Celebrity Cars in Las Vegas has it on sale for $1.5 million.) Frank jumped out of his car but Knight, whose skull had been pierced by a bullet fragment, hooked a U-turn and sped off with several other cars in hot pursuit. Slowed by a blown-out tire, he was finally forced to stop. Frank caught up, as did police and paramedics.

“As soon as everybody came to a stop, bam, the doors all opened up, pretty much everybody got out, and I thought for sure it was going to be a shooting,” retired Las Vegas Metropolitan Police sergeant Chris Carroll, who was on bicycle patrol at the time and was the first officer on the scene that night, tells E! News.

“At the time we have no other information than that there’s been a shooting and that these cars are running from the police. I figured one of [the people in] the cars was the shooter, at least. We don’t know who’s chasing who, or why. So when they got there I pulled out my gun and I was trying to tell everybody, yelling at ’em, to get down on the ground. Some of them did and some of them didn’t. It was kind of a passive resistance. Some of them kind of looked at each other, like, ‘do we listen to him? What are we going to do here?’ They kind of unwillingly complied.”

Carroll noticed that one person was still in the passenger seat of the BMW and he approached the car, telling the man to get out. At first he couldn’t get the car door open, and Suge Knight then got out. He’s “running around yelling, blood flying out of the side of his head but he’s acting like he’s not hurt at all,” Carroll recalls. “I had to point my gun at him and say, ‘get back.'”

When he finally got the door open, he could see that the man—whom he’d soon find out was Tupac—was in bad shape.

The rapper had been shot four times. According to Tayannah Lee McQuillar and Frank Johnson‘s 2010 biography Tupac Shakur, once he was lying on the pavement, he said to Alexander, “Frank, I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe.” And that was it.

Carroll has a different memory of Shakur’s last words.

“We have something called a dying declaration, where if someone is able to tell you, while they’re dying and they believe they’re going to die, who killed them, that’s admissible in court,” he explained to E! News. “It’s not hearsay. So I asked him, ‘What happened? Who shot you? Who did this?’ And he was just kind of ignoring me. He was trying to yell back and forth to Suge. Suge was yelling at him, ‘Pac, ‘Pac!’ he kept yelling, and Tupac was trying to yell back but he couldn’t’ really get a breath together.

“I was still trying to ask him who shot him, what happened, and finally he went from kind of swirling and trying to yell at Suge to all of a sudden in an instant going to a feeling like he couldn’t do it anymore,” Carroll continued. “And he just kind of went back and…I could just see him going into a relaxed state. And he looked at me and I thought I was actually going to get some cooperation, and he got a breath together and I said, ‘Who did this?’ He looked at me and he went, ‘F–k you.’ And that was it.

“After he said that, his eyes rolled back in his head, he was gurgling, and he never regained consciousness again, so that was the last thing he ever said.”

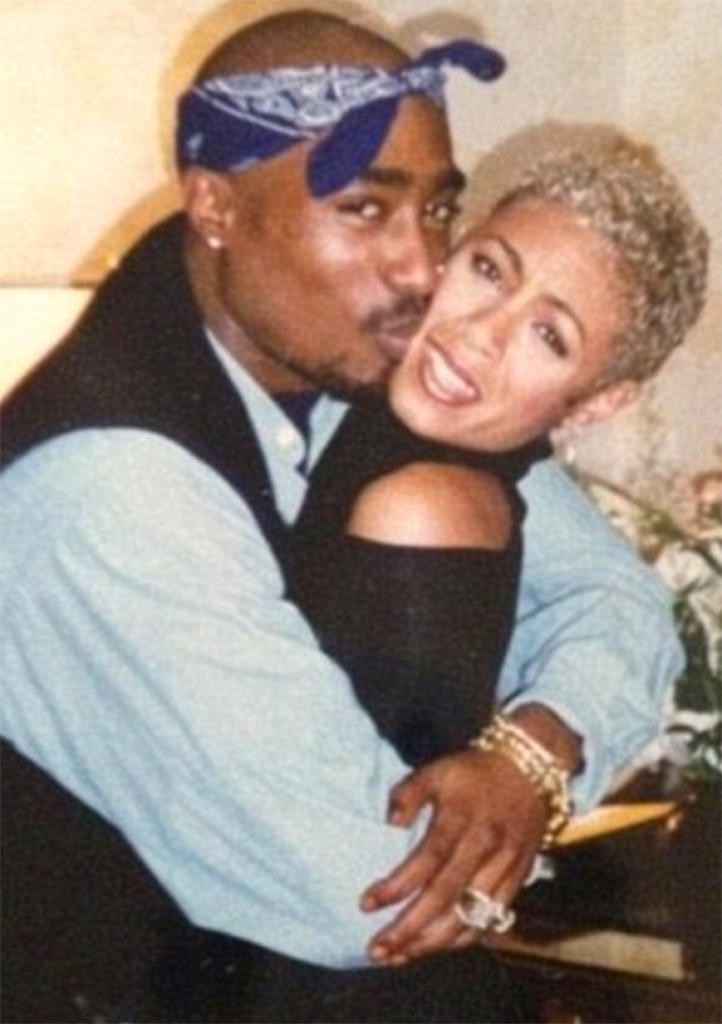

Jeff Vespa/WireImage.com

“I knew we should’ve never gone to Vegas that night,” Kidada Jones, daughter of Quincy Jones and Peggy Lipton and older sister of Rashida Jones, wrote in a portion of her father’s 2001 autobiography. “I had a horrible feeling about it. I’ve gone over it in my mind a million times. It wasn’t supposed to happen. We weren’t supposed to be there.

“It was the worst possible thing that could have happened—I still to this day don’t know who shot him. I wasn’t able to say goodbye. It’s not something that should happen to anyone.”

Tupac had told her to stay in the hotel that night, that there had been a fight earlier, and it wasn’t safe.

Shakur underwent emergency surgery at University Medical Center but never woke up. He spent six days on life support and died at 4:03 p.m. on Sept. 13, 1996, after his mother consented to turn off the machines.

He was 25 years old.

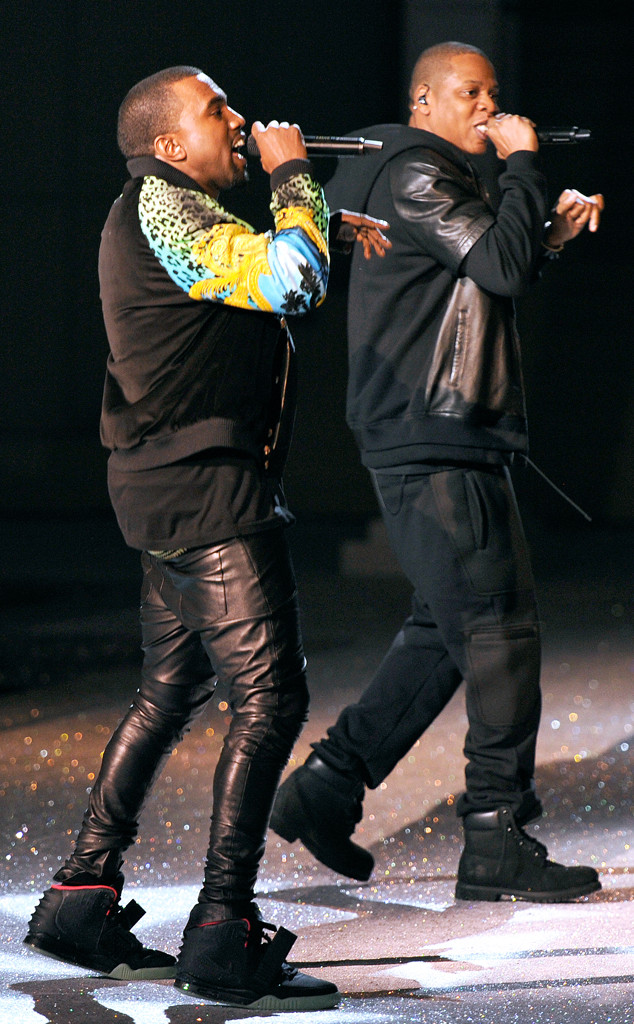

TIMOTHY A. CLARY/AFP/Getty Images

Tupac Shakur’s legacy has been a fluid one. Everything from books, documentaries and biopics to his appearance as a hologram at Coachella and endless dissections and reexaminations of the music he left behind, plus the sporadic unearthing of never-before-heard music over the years, has added endless layers to the Tupac mythos. His influence can be felt in the work of artists from Eminem, Kanye West and Kendrick Lamar to those who weren’t even born yet when Shakur died.

West, saying he had been watching some of Shakur’s old interviews, told Interview in 2014, “I watched them, and one of the things that Tupac kept saying is that he wanted thugs to be recognized. Now Jay-Z is a multi-hundred-millionaire who came from the streets, so Tupac’s mission, in a way, has been realized.”

Despite being treated like a cultural deity, Tupac Amaru Shakur, named after an 18th-century Peruvian revolutionary (whose namesake was the last emperor of the Incas), was of course no saint. But he was, by all accounts, a deeply sensitive and intuitive artist, a voracious reader, poet and visionary who brought gravitas to every lyric and radiated charisma. He and his sister Sekyiwa were raised by a single mom, Afeni Shakur, a member of the Black Panther Party who had been in and out of jail, including when she was pregnant with her son.

She worked as a paralegal in the Bronx but, after that job went away, she struggled to put a roof over their heads. A boyfriend who was an associate of a local drug lord went to prison for credit card fraud and died behind bars. Eventually the family moved to Baltimore, where Afeni got a job as a data processor.

Until he enrolled at the Baltimore School for the Arts, where tuition was free for local kids, Tupac had operated under the assumption that white people weren’t to be trusted.

At school he and the future Jada Pinkett Smith became friends when, as the actress put it in 2017, she was heading out of “the life” and Shakur was heading in.

“I know that most people want to always connect it in this romance thing, and that’s just because they don’t have the story,” Pinkett Smith said on Sway in the Morning. “But it was based in survival, how we held each other down…When you have somebody that has your back when you feel like you’re nothing, that’s everything.”

In the middle of his junior year of high school, the family was evicted from their apartment and Afeni packed up and moved them across the country to Marin City, Calif. But she soon sank into crack addiction and her 17-year-old son moved out and lived with some other boys in an abandoned apartment while he worked in a pizza parlor and went to class. He dropped out just shy of graduation.

Not making it as a small-time dealer (“the drug dealer said give me my drugs back ’cause I didn’t know how to do it,” he said), he was already rapping in front of friends and whoever would listen, gaining a local reputation that preceded him when he met Leila Steinberg, a music promoter who took him under her wing and became his first manager, as well as friend and mother figure when he was so in need of one.

In a 2010 interview with Chicago Now‘s GoWhere Hip-Hop blog, Steinberg remembered Shakur as “just an incredible spirit and an awesome young man. On first meeting, you meet people and you connect with them. He’s one of the deepest connections in my life and he will always be. Yeah, Pac was definitely a connection that was one of a kind.”

Steinberg said that 24/7, Shakur’s production company that he never got a chance to do much with, was an apropos name because its founder was always going, all the time.

“2Pac was very, very difficult and exciting at the same time,” she said. “You couldn’t tell him anything; he knew everything. He was incredibly stubborn, with incredible vision. He had a work ethic unlike no other that I have met, to date…His body…different people have different requirements. And he literally did not require the same amount of sleep. It’s like he worked on some other level, where he tapped into another energy source and has this desperation to complete what he felt he was here to do.”

Steinberg hooked Shakur up with his next manager, Atron Gregory, who got the talented teen started as a roadie for Digital Underground. Pretty soon he was joining him onstage, but he was a volatile presence.

“We said, ‘OK, we can’t use you,'” frontman Gregory “Shock G” Jacobs, Shakur’s closest friend in the group, told Vanity Fair in 1997. “Two hours later, Tupac’s back, like nothin’ happened. It was like that all the time. He’d flip on you, then the incident didn’t exist.”.

Shakur was featured on Digital Underground’s album This Is an EP Release, debuting his solo skills on “Same Song” and appearing in the video.

Funnily enough, Shakur’s first onscreen appearance came with Digital Underground in the 1991 comedy Nothing but Trouble, starring Dan Aykroyd and Chevy Chase; the group performs “Same Song” to get Aykroyd’s judge to release them from traffic court.

Shakur struck out on his own and was signed by Jimmy Iovine‘s Interscope Records in 1991, further cementing Iovine’s own reputation as a visionary. Tupac’s first single, “Trapped,” was about a young black man getting into a confrontation with a police officer, who then fires at him and the man fires back. Chased down and cornered by police afterward, he raps, “I’d rather die than be trapped in the living hell.”

On Oct. 17, 1991, a few weeks after the hit single was released, two white cops stopped the rapper for jaywalking in Oakland and, according to Shakur, they hassled him instead of writing him a ticket and sending him on his way. He said that he swore at them, then they wrestled him to the ground, choked him out and he was jailed for resisting arrest.

“They sweated me about my name, the officers said, ‘you have to learn your place,'” Shakur recounted at a press conference that November.

It was his first trip to jail and, while he was adamant about having been mistreated by the cops, his reputation split into two right there—hardworking black artist calling out the cops for violating his civil rights, five months after the beating of Rodney King vs. authority-flouting criminal who had no respect for law enforcement.

Both narratives boosted the release of Shakur’s debut algum, 2Pacalypse Now, on Nov. 12, 1991. The album went platinum, earning Shakur a litany of lifelong fans and the ire of the fearful who scorned the music as detrimental to young minds, as well as activists who worried Shakur was just a walking glamorization of the societal ills he rapped about. (Shakur later settled a $10 million lawsuit he filed against the city of Oakland for a reported $42,000.)

In a 1992 interview with E! News, Shakur drew a distinction between the violence rapped about in music and seen in movies that politicians were so fond of excoriating and the violence taking place on the streets every day.

“It’s an adventure world that we’re creating,” he said. “What we’re doing is using our brain to get out of the ghetto, any way we can, so we tell these stories…and they tend to be violent, because our world tends to be filled with violence.”

“In my rhymes,” he explained, lyrics about shooting back at the police “vents that anger, ’cause I can fire back at the police and won’t go to jail for life.” And ultimately his music was mainly talking about “the oppressed rising up against the oppressor…So the only people that’s scared are the oppressors. The only people who have any harm coming to them are those who oppress, simple as that.”

The emergence of T.H.U.G. L.I.F.E. (The Hate U Give Little Infants F–ks Everyone), his mission statement to curb the drug use and violence plaguing the inner cities, was as polarizing as you’d expect.

“It’s not thugging like I’m robbing people,” he told MTV, according to Michael Eric Dyson‘s 2006 book Holler if You Hear Me: Searching for Tupac Shakur. “That’s not what I’m doing. Part of being a [thug] is to stand up for your responsibilities and say this is what I do even though I know people are going to hate me and say, ‘It’s so politically un-correct,’ and ‘How could you make black people look like that? Do you know how buffoonish you all look with money and girls and all of that?’ That’s what I want to do. I want to be real with myself.”

Shakur hardly eschewed the good life, but he disdained what to him was the insatiable need for more being sewn into the fabric of society, and he decried the glaring divide between the white and black experience in this country.

He told MTV News in August 1992, “Everybody’s like you get taught that from school, everywhere, big business, if you want to be successful, you want to be like Trump, ‘gimme, gimme gimme, push push push push, step-step-step, crush-crush-crush,’ that’s how it all is. And it’s like nobody ever stops. I feel like instead of us just being like ‘slavery’s bad…bad whitey,’ let’s stop that.

“And everybody’s smart enough to know we’ve been slighted, and we want ours. And I don’t mean by ours like ’40 acres and a mule, ’cause we’re past that. But we need help. For us to be on our own two feet, meaning youth or ‘us’ meaning black people, whatever you want to take it for…because we have been here, we have been a good friend…and now we deserve our payback. You got a friend that you don’t never look out for…America’s got jewels and they paid and everything, and they’re lending money to everybody except us.”

He continued, “If this is truly a melting pot and a country where we care about everybody, Lady Liberty got her hand like this [he raised an imaginary torch], she really love us, then we really need to be like that.”

Shakur’s second album, Strictly 4 My N.I.G.G.A.Z., came out in February 1993 and also went platinum.

The video for “Keep Ya Head Up” was dedicated to Latasha Harlins, a black teenager who was killed in 1991 by Korean liquor store owner Soon Ja Du. Du said Harlins was trying to steal a bottle of juice. The 15-year-old had put it in her backpack and witnesses said the girl had $2 in her hand to pay. Du grabbed Harlins’ arm and Harlins hit her in the face, knocking her down. She dropped the juice at the counter and headed for the door.

Du shot the teen in the back of the head. She was convicted of voluntary manslaughter and was sentenced to probation and community service, and fined $500.

Tupac Shakur was fast becoming the voice of a black community that was tired of coming out on the losing side. And yet he wasn’t always so serious. He also liked partying and smoking weed, and living the life of a beloved rapper.

As Arsenio Hall commented when Shakur appeared on his show in 1993, it seemed as though there were “two Tupacs.”

At the same time, however, a third Shakur started to emerge.

He was arrested twice in Los Angeles in March 1993, on March 11 for carrying a concealed weapon and on March 13 after allegedly attacking a limo driver who had driven him to a taping of In Living Color. Shakur told a judge that he thought the driver may have been reaching for a gun. Those charges were dropped; he was convicted on the gun charge.

In April 1993 he spent 10 days in jail in East Lansing, Mich., after swinging at another rapper with a bat during a concert at Michigan State, nearly causing a riot in the audience.

In Atlanta in the early a.m. hours of Oct. 31, 1993, Shakur got arrested for shooting and wounding two off-duty police officers. Prosecutors charged that the two cops had been crossing the street with their wives when two cars ferrying Shakur and his entourage almost hit them and a confrontation ensued.

In his defense Shakur said he had pulled over because he saw two white guys harassing a black motorist and he had no idea they were cops. The assault charges against Shakur were dropped after it was determined that one of the guns aimed at him had been seized in a drug bust and stolen from an evidence locker, and the officers had been intoxicated.

While Shakur’s star in the hip-hop community was rocketing ever higher, he was also increasingly in demand in Hollywood. His acting career began with his role as a troubled teen in the 1992 drama Juice. The New York Times called him the movie’s “most magnetic figure.”

That was followed by 1993’s Poetic Justice, co-starring Janet Jackson. He guest-starred on the Cosby Show spin-off A Different World, then landed starring roles in the basketball drama Above the Rim and the crime dramas (all released posthumously) Bullet, Gridlock’d and Gang Related. He dated Madonna and became pals with Mickey Rourke.

It was during the filming of Poetic Justice that Shakur first heard a song called “Party and Bulls–t” by an up-and-coming rapper named Christopher Wallace—or Biggie Smalls on the street—who was affiliated with New York-based Bad Boy Records, started by Sean “Puff Daddy” Combs. Shakur saw Biggie perform in Maryland and introduced himself. They became fast friends and ended up collaborating on songs like “Runnin’ (Dying to Live)” and “House of Pain.” Biggie even stayed with Tupac on trips to L.A.

Meanwhile, in New York Shakur had also befriended a club promoter named Jacques “Haitian Jack” Agnant, said to be an inspiration for Birdie, the charismatic, basketball-playing thug Shakur plays in Above the Rim.

On Nov. 18, 1993, 19-year-old Ayanna Jackson, who had had a couple of sexual encounters with Shakur after meeting him at a nightclub several nights prior, was invited to the rapper’s suite at the Parker Meridien. When she arrived, several other people were there, including Agnant and Charles Fuller, Shakur’s road manager.

Shakur later told Vibe that two other men came into the bedroom when he was in there with Jackson and, not wanting to tangle with them, he left and passed out on the couch.

Jackson, however, maintains that she was sexually assaulted by multiple men that night, including Shakur. The rapper and Fuller ended up being charged with first-degree sexual abuse, sodomy and illegally possessing a firearm. (Agnant was also charged and tried separately. A fourth man who was supposedly there was never located.)

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Shakur maintained his innocence, but the charges against him had finally punctured the Teflon that had seemed to surround him throughout his previous run-ins with the law.

“He was a sensitive guy. He didn’t know if he wanted to be a thug or revolutionary,” John Singleton recalled to Vibe in 2011. “I still dream about the movies me and Tupac would have made. I wrote Higher Learning for him. He was playing the Omar Epps role. The original cast to Higher Learning was supposed to be Tupac, Leonardo DiCaprio, Gwyneth Paltrow and Juliette Lewis. ‘Pac ended up getting in trouble and then all that stuff happened in New York. It was logistically impossible.”

Also in 1993 Shakur was fired from Menace II Society after becoming hard to deal with on set and he ended up involved in an attack on co-director Allen Hughes at a music video shoot. While awaiting trial in the rape case, Shakur was sentenced to 15 days in jail in March 1994 for assault and battery. At the time, per the Los Angeles Times, there were four cases pending against Shakur in three states, including the then yet-to-be closed Atlanta shooting.

“If ‘Pac had been in the movie he would’ve outshined everyone,” Hughes told IndieWire in 2013. “It would’ve thrown the whole axis of the movie off if Tupac was in it, because he was bigger than the movie.”

Shakur had been nominated for an NAACP Image Award for Poetic Justice and National Political Congress of Black Women leader and anti-gangsta rap crusader C. DeLores Tucker picketed the show for not rescinding his nomination. (Tucker, who died in 2005, unsuccessfully sued his estate in 1997 after being name-checked on All Eyez on Me.)

He also met his future wife, Keisha Morris, in New York while awaiting trial. In school at the time working on a degree in criminal justice, Morris chose to not go to court with him, but she believed in his innocence.

Tim Mosenfelder/Getty Images; Jane Caine/ZUMAPRESS.com

With opportunities drying up, Shakur was fast going into debt and needed an infusion of cash. He agreed to rap on a record being made by Little Shawn, an up-and-comer signed to Andre Harrell‘s Uptown Records and managed by James Rosemond (aka “Jimmy Henchman”), who knew Agnant.

In November 1994, Shakur suggested in an interview with the New York Daily News that Agnant had set him up in the rape case, reportedly calling him a “hanger-on.” He had also seen Agnant and Biggie hanging out.

On Nov. 30, Shakur went to the NYC recording studio Quad to cut the track for Little Shawn. He was with his sister’s boyfriend Zayd; Live Squad rapper Randy “Stretch” Walker, a mutual friend of his and Biggie’s; and Stretch’s friend Fred.

When they got there, there was a guy in army fatigues outside and another in the lobby, neither of whom Shakur knew, but he assumed they worked security for Biggie. On their way to the elevator, the two men pulled out guns and told everyone to get down and take off their jewelry. Shakur ended up getting shot five times.

Still, he made his way to the elevator and went upstairs, where a group was assembled, including Combs, Biggie and Harrell. According to some accounts, the police who arrived at the scene were the same three who had arrested Shakur for sexual assault, including one who had just testified at his trial. (Shakur told Vibe he recognized the cop after he got shot.) But former NYPD detective Bill Courtney, who had worked with a task force quietly set up to monitor the hip-hop community, told XXL magazine in 2011 that it wasn’t the same cops.

Courtney did, however, believe that the shooting was payback for something. (In 2011, a prison inmate serving a life sentence for murder wrote to AllHipHop.com claiming that Jimmy Rosemond hired him to shoot Shakur at Quad; Rosemond’s attorney brushed that off as nothing but an inmate’s attempt to get his sentence shortened.)

Shakur was taken to Bellevue Hospital but soon checked himself out to recuperate at the home of a friend, the actress Jasmine Guy.

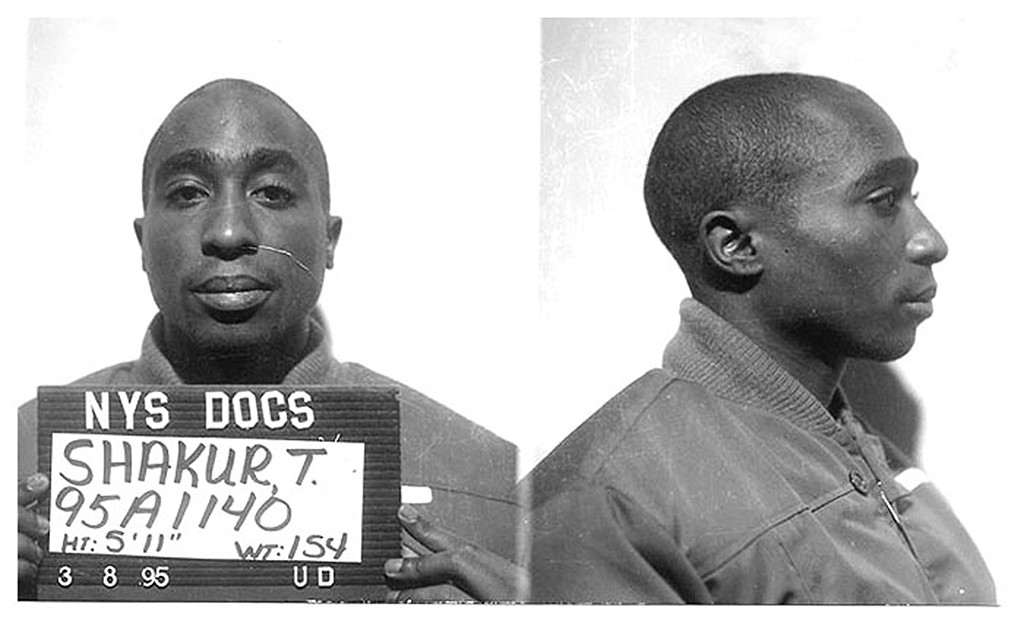

On Dec. 1, 1994, Shakur, bandaged and sitting in a wheelchair less than a day after being shot, and Fuller were found not guilty on the gun and sodomy charges, but were found guilty of three counts each of sexual abuse. In February 1995 Shakur was sentenced to 1 1/2 to 4 1/2 years in prison. Fuller, whom the judge determined had arranged the date and then stood by as Ayanna Jackson was attacked, was sentenced to four months in jail and five years’ probation.

Shakur apologized to Jackson, but added, “I’m not apologizing for a crime. I hope in time you’ll come forth and tell the truth.”

“Maybe the fear, maybe other people, the influence around him, maybe he felt he could not intervene,” Jackson told VladTV in September 2018. She has never “come forth” with any story other than her first one. Though Shakur was found guilty of abusing her, she said, “There is no justice in that. Not at all.”

Shakur did tell Vibe‘s Kevin Powell from jail, while awaiting sentencing in 1995, “Never did nothing…But I know I feel ashamed—because I wanted to be accepted and because I didn’t want no harm done to me—I didn’t say nothing.” (Incidentally, Powell sued the producers of the 2017 Tupac biopic All Eyez on Me, claiming the script was basically ripped right from a series of articles he wrote about the rapper.)

Agnant, who pleaded down to a misdemeanor conviction and received probation, was later called out by Tupac on the 1996 diss track “Against All Odds.” He told HipHopWired in 2015 that he believes Shakur was ordered to call him out, that he and the rapper had been “like brothers.”

“Then later on other things lead to other things and then people put things in his head, which created a bad blood between him and me,” Agnant, who was deported to Haiti in 2007, said. “But I never had any bad blood towards him though. A lot of those things will get cleared up sooner or later. I actually had nothing to do with what happened to Pac. I never played a role in anything.”

About the rape case, “The thing is Pac did nothing to that girl, neither did I and neither did anyone else.”

Tupac Shakur went to jail in February 1995.

His third album, Me Against the World, recorded after the shooting and featuring classics like “Dear Mama” and “So Many Tears,” was released the following month and debuted at No. 1 on the Billboard 200. (It was nominated for Best Rap Album at the 1996 Grammys.) Shakur then married the devoted Keisha Morris on April 4. (The union was annulled in 1996.)

While in jail, Shakur made it clear he believed he’d been betrayed by people he trusted.

“Be to yourself, stay to yourself, trust nobody,” Shakur said in another prison interview. “Trust nobody…My closest friends did me in, my closest friends, my homies—people who I’d have took care of their whole family, I’ve have took care of everythin’ for ’em, looked out for ’em, put ’em in the game, everything—turned on me.

“Fear is stronger than love, remember that. Fear is stronger than love. All the love didn’t mean nothing when it came to fear. So it’s all good, I’m a soldier, I always survive. I constantly come back…only thing that can kill me is death. That’s the only thing that’ll ever stop me is death. And even then, my music’ll live forever.”

Needless to say, Shakur’s relationship with Wallace, aka Biggie Smalls, aka Notorious B.I.G., had been irreparably damaged.

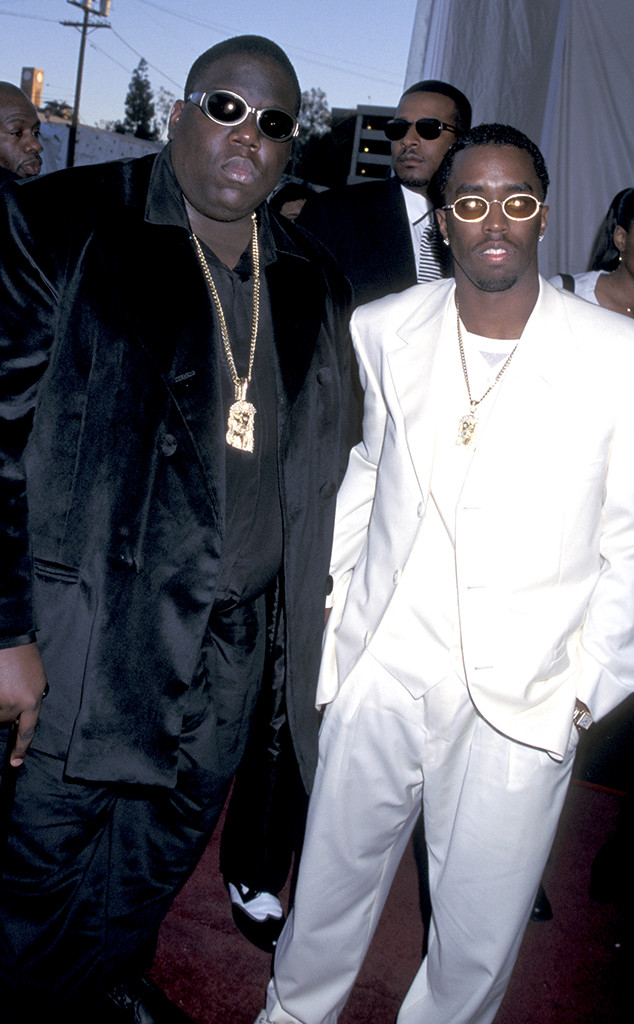

But it wasn’t the beef between them that initially pitted East Coast vs. West Coast. The general consensus is that it was Suge Knight taking a swipe at “Puff Daddy” Combs during the 1995 Source Hip-Hop Music Awards at Madison Square Garden that August, when Shakur was still in prison, that lit the fuse. Knight reportedly said, “Any artist out there who wants to be an artist and stay a star, and don’t wanna have to worry about the executive producer trying to be all in the videos, all on the records, dancing—come to Death Row.”

The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images)

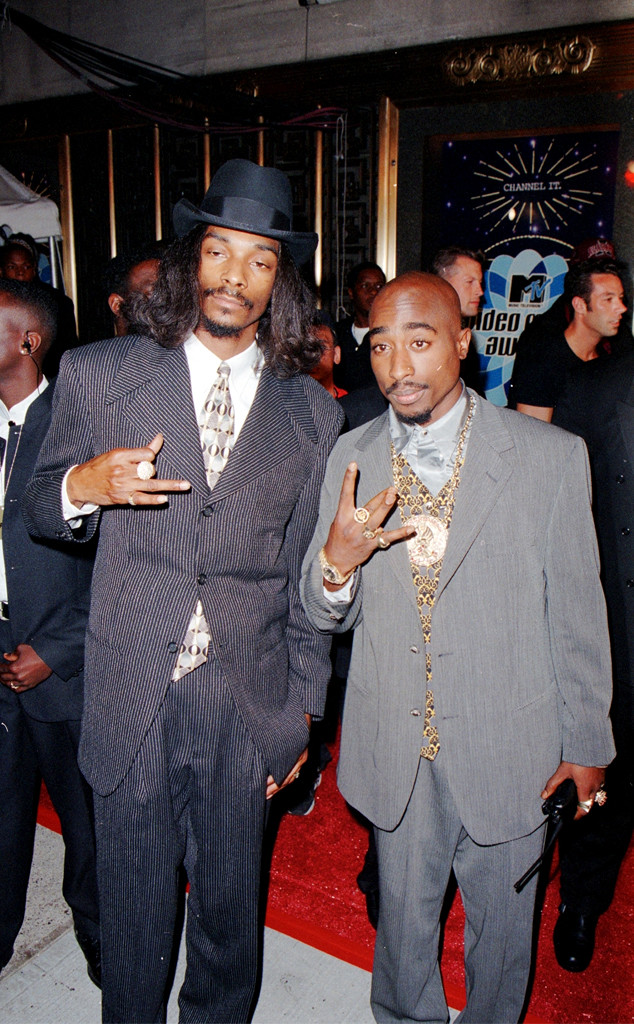

Then Death Row artist Snoop Dogg got on stage to a chorus of boos and inquired, “The East Coast ain’t got no love for Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg and Death Row? Y’all don’t love us?…We know y’all East Coast…We know where the f–k we at…So let it be known then!”

Not long after, Knight’s friend Jake Robles was shot and killed in Atlanta, and a witness fingered Combs’ bodyguard, Anthony “Wolf” Jones. No one was charged and, in 2001, when the subject came up again when both Jones and Combs were on trial related to a nightclub shooting in New York, their attorneys stated that their clients had “absolutely nothing” to do with Robles’ death.

Wolf Jones was shot to death in Atlanta in 2003.

Meanwhile, Knight had visited Shakur several times in prison and ended up posting the $1.4 million bail that got the rapper released early while he appealed his case. Shakur then signed a three-album, $3.5 million deal with Death Row Records, which had altered the hip-hop hierarchy in 1992 with Dr. Dre’s triple-platinum-selling debut solo album The Chronic.

Raymond Boyd/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

When Shakur got out of prison (and into a white limo and then onto a private jet to take him to L.A.) in October 1995, he was stepping right into a war zone.

But he also got right back to work on his fourth album. The first single, released that December, was “California Love,” featuring Dr. Dre. The song, Tupac’s most enduring commercial hit, went to No. 1 on the Billboard 100 and was nominated for two Grammys.

Shakur also reportedly felt that Knight’s connections could help keep him safe from the various enemies he’d acquired over the years, which now included Biggie Smalls. He’d poked the bear by publicly accusing Wallace of co-opting his style (a jab hip-hop connoisseurs have since disputed as not having much weight behind it).

And yet he also had to nurture the commercial side of his life. “I got shot five times by some dudes who were trying to rub me out,” Shakur told the Los Angeles Times. “But God is great. He let me come back. But when I look at the last few years, it’s not like everybody did me wrong. I made some mistakes. But I’m ready to move on.”

In November 1995, exactly one year after the Quad shooting, Stretch Walker was shot to death in Queens. Tupac, who had started to wonder if his friend had set him up, denied having anything to do with it.

Shakur had originally tried to insist there was just an issue between him and Wallace, denying that there was some big Coast vs. Coast beef going on, but he eventually started taking more digs at the East Coast scene in general—and then he kicked it up a notch.

Shakur and Snoop Dogg appeared with Knight on the cover of the New York Times Magazine in January 1996. Knight said in the article that Notorious B.I.G.’s wife, Faith Evans, had bought the outfit Tupac was wearing, as well as “some other stuff.” Asked how he thanked her, Shakur said, apparently lasciviously, “I did enough.”

Biggie, who ended up getting booed at the 1996 Soul Train Awards held in Los Angeles that March, was by many accounts positively livid.

When All Eyez on Me—hip-hop’s first double album—came out in April 1996, it was a critical and commercial smash.

One song stood out in particular, however, for not having ‘Pac’s usual socially conscious bent—”2 of Amerikaz Most Wanted,” a duet with Snoop. The music video, filmed in the spring of 1996, features a bloody Tupac, fresh from being shot, walking in on two guys named “Buffy” and “Piggie,” and Buffy’s saying, “He’s gone, baby, you the man.”

They beg for their life. Tupac says, “I ain’t gonna kill you. We was homeboys once, Pig. Once we homeboys, we always homeboys.” Then he steps aside and the scene cuts to yellow police tape.

“All names have been changed to protect the innocent,” the video taunts at the beginning.

Mark Davis/BET/Getty Images for BET

“Why would I set a n—a up to get shot?” Combs told Vibe in 1995. “If I’ma set a n—a up, which I would never do, I ain’t gonna be in the country, I’ma be in Bolivia somewhere.”

The man who would soon be known as “Diddy” said that Tupac knew who shot him but he was busy making trouble with them. “If you ask him, he knows, and everybody in the street knows, and he’s not stepping to them, because knows that he’s not gonna get away with that s–t. To me, that’s some real sucker s–t. Be mad at everybody, man; don’t be using n—as as scapegoats. We know that he’s a nice guy from New York.

“All s–t aside, Tupac is a nice, good-hearted guy.”

Meanwhile, at least one beef in Shakur’s life had ended surprisingly happily. In a 1993 interview with The Source, the rapper had slammed interracial couples, calling Quincy Jones “disgusting” for being with white women and making “f–ked up kids.”

Rashida Jones, 17 at the time, wrote a letter to The Source defending her father and asking Tupac, “Where the hell would you be if Black people like him hadn’t paved the way for you to even have the opportunity to express yourself? I don’t see you fighting for your race. In my opinion, you’re destroying it and s–tting all over your people.”

Kidada later saw Tupac at a club and he went up to her to apologize. “‘I didn’t mean that about your dad or you. I didn’t see you as real human beings. Now that I see you…'” she recalled him saying in her dad’s memoir. “He was all game. He was trying to get a play, let’s face it, but I liked him.”

They started dating and eventually ran into Quincy Jones at a Jerry’s Deli one night in L.A. He came up, clapped his hands on Shakur’s shoulders and asked him to have a chat. “They stood up and hugged when it was over and they got along fine from them on,” Kidada wrote.

She and Shakur lived together for four months and were talking about getting married before he was killed.

Much like Notorious B.I.G., Tupac Shakur frequently referenced his own demise—whether he truly sensed it was imminent or not. After prison he took to wearing a bullet-proof vest around and never went out without at least one bodyguard.

“I know one day they’re gonna shut the game down but I gotta have as much fun and go around the board as many times as I can before it’s my turn to leave,” he told Oakland’s KMEL radio station.

On June 4, 1996, he released the diss track “Hit Em Up,” in which Shakur raps, “That’s why I f–ked your bitch you fat motherf–ka.” Michael Eric Dyson called it “the most bitter, vindictive, vengeful battle rap and diss song of all time…It was vicious and it was powerful and compelling at the same time.” (In the May 1996 issue of Vibe, Evans denied ever sleeping with Shakur.)

After “Hit Em Up” came out, bodyguard Frank Alexander told his boss he’d need reinforcements to protect Tupac. The rapper laughed that off. He was busy touring with Tha Dogg Pound, shooting Gridlock’d, making a video a week and working on his fifth studio album, The Don Killuminati: The Seven Day Theory, which—years ahead of artists ranging from Beyoncé to Nicki Minaj to Garth Brooks—he attributed to an alter ego, Makaveli.

The album came out Nov. 5, 1996, two months after Shakur was killed.

The murder of 24-year-old Biggie Smalls, on March 9, 1997, proved a depressing, not altogether surprising epilogue to the story of Tupac Shakur’s short life while also assuring Notorious B.I.G.’s own legend would only grow.

The enduring fascination surrounding the inextricably linked cases has resulted in numerous examinations of what happened, including last year’s USA limited series Unsolved: The Murders of Tupac and Notorious B.I.G., starring Marcc Rose as Shakur and Wavvy Jones as Biggie.

Rose, who also played Shakur in the 2015 film Straight Outta Compton and was 4 when Tupac was killed, said he thinks both rappers would’ve still been at the top of their game had they lived.

“Hip-hop has changed so much over the years, I don’t think they’d rock with most of the music that gets played on radio today,” he told The Source. “There aren’t messages being told the way they used to anymore. I feel they would’ve changed that.”

Executive producer Anthony Hemingway also worked on American Crime Story: The People v. O.J. Simpson, and Unsolved similarly examined the Los Angeles Police Department’s twisted history with celebrity, race relations and internal corruption.

Jimmi Simpson took on the role of late LAPD Detective Richard Poole, who eventually came to the belief that Suge Knight orchestrated both murders, and Josh Duhamelplayed Detective Greg Kading, who detailed exactly who he believes is responsible in his 2011 book Murder Rap: The Untold Story of the Biggie Smalls and Tupac Shakur Murder Investigations and who served as an executive producer on Unsolved.

Orlando Anderson, the man Shakur had tussled with hours before he died, was considered a prime suspect in his murder—at least by L.A. police—but nothing ever came of it. Shakur’s mother filed a wrongful death lawsuit against Anderson in September 1997, alleging that he pulled the trigger and was later seen carrying the same kind of gun that killed her son, a .40-caliber Glock.

In May 1998, Anderson was killed along with another man in what police deemed an unrelated gang shoot-out in Compton, Calif.

Afeni Shakur died in 2016, having spent the rest of her life after her son’s death tending to his legacy. She produced the 2003 documentary Tupac: Resurrection and founded Amaru Entertainment/Amaru Records—not because she had wanted to be a producer or a music mogul, she said, but because she was compelled to do so.

“Whatever it is I’m doing I do because my son was murdered, and he was not able to complete his work,” Afeni said in a 2003 interview. “So as his mother, my whole job and responsibility is to see to it that that happens for him, and I do that with love.”

She was forever frustrated, however, that her son’s killer was never brought to justice.

Among the theories is that Suge Knight was either the target or was behind both murders, having offed Tupac to prevent him from leaving Death Row to start his own label.

Chris Carroll, the first cop on the scene of Shakur’s shooting, didn’t buy the latter.

“I’ve heard all the conspiracy theories that have come out, that Suge had something to do with it,” he told Vegas Seven in 2014. “And I’ll tell you, that didn’t happen. And one reason is: You don’t hire somebody to kill the guy who’s sitting next to you. And second of all: When we were at the scene, and he was yelling at Tupac, it was clear he had legitimate concern for him. It wasn’t acting; you could see it was the heat of the moment. This is not the guy who had him killed; it’s ridiculous.”

Like the LAPD, the Vegas police were accused of not thoroughly investigating Shakur’s murder for whatever reason—a theory Greg Kading finds illogical.

“It’s going to look worse if you don’t solve it,” he told E! News in a 2018 interview. “If there’s quick and immediate justice, and you make it clear that gang members aren’t going to come to Las Vegas and kill people, that’s the impression you want to make. You don’t leave it unsolved if you want to create a safe environment.” (Shakur associated with gang members, but he himself was not one, Kading reiterated.)

There was even a far-out conspiracy theory that Quincy Jones was behind Shakur’s murder. Asked if he was aware of it, Jones told the New York Times in 2012 that he did. “The people who say I wanted to have sex with him,” the 28-time Grammy winner said. “Man, this is the biggest age of haters I have ever seen in my life. I’ve been called a blonde-lover, a pedophile, gay, everything. I don’t care, man. Imagine my daughter being engaged to Tupac and me trying to make love to him? And I’m not into no men, man. I’m a hard-core lesbian. Are you kidding? All my life, all my life.”

Then there were the optimistic souls who were convinced Shakur faked his own death to get himself out of the game. Not since Elvis Presley have more people believed in the persistent existence of a man who was gone way before his time.

Far more prevalent, due to their widely publicized beef, was speculation that Notorious B.I.G. was behind Shakur’s murder and in turn Knight masterminded Biggie’s murder. Numerous sources laid out various theories to the Los Angeles Times, including that Biggie had been in Vegas at the time and had put a $1 million hit on his rival. (Biggie’s mother, Volletta Wallace, told Rolling Stone in 2010 that the idea her son had masterminded the Vegas attack was “so ridiculous.”)

Jim Smeal/WireImage

Combs called the theory that he commissioned Tupac’s murder, as proposed by Kading in his 2011 book, “pure fiction and completely ridiculous.” According to Kading, Orlando Anderson’s uncle, Crips member Duane “Keffe D” Keith Davis, told police in 2008 that he was sitting in the passenger seat of the white Cadillac from which the fatal shots were fired at Tupac. He said Anderson shot at the BMW from his perch in the backseat of the Cadillac, and Combs ordered the whole thing. (Keffe D had told the FBI in 1997 that his nephew wasn’t involved.)

“I take the word of the street gang cops in Compton,” Cathy Scott, author of the 1997 book The Killing of Tupac Shakur, tells E! News. Tupac was shot at 11:15 p.m. on a Friday. “That next day, Saturday, Orlando Anderson, they drove home in the Cadillac, he drives home, gets back into Compton, and goes all over the street telling everybody, ‘I shot ‘Pac, I shot ‘Pac.’ He was bragging about it.”

Also according to Kading’s Murder Rap, Knight’s girlfriend “Theresa Swann” (an alias used in the book for her protection) had said Knight gave her $13,000 to give to his associate Wardell “Poochie” Fouse, and tell him in no uncertain terms that he wanted Biggie dead. Several sources fingered Fouse as the trigger man, Kading wrote.

Poochie Fouse was shot and killed in July 2003 while riding his motorcycle in Compton, caught up in a feud between different Blood factions, according to police. The LA Times reported that Poochie’s death made four of Knight’s closest associates killed since 1997.

Asked in August 2003 if he feared for his own life, Knight told the Times at the Peninsula Hotel in Beverly Hills, “I don’t believe anyone is hunting me. But even if they were, so what?…The only guarantee a man has in life is that you are born to die. I’m from the ghetto, where black men get killed every day.”

Kading wrote that he was about to lay out his findings when higher-ups at the LAPD pulled him off the case in 2009. (Police told the LA Weekly in 2011 that the investigation into both murders was “active/ongoing.”) He had been part of a police task force put together in 2006 to solve Biggie’s killing, in no small part because Volletta Wallace had sued the city of Los Angeles for millions over her son’s death.

No versions of her lawsuit named Suge Knight—who was in prison for violating probation on a previous assault charge when Biggie was killed and didn’t get out until 2001—as a defendant. One of the first people named, however, seemingly thanks to a theory espoused by Richard Poole, was David Mack, a cop who had been investigated in the LAPD Rampart corruption scandal and who had ties to Knight, and associate Amir Muhammad, whom police also suspected at one point had pulled the trigger on Notorious B.I.G. Both men were dismissed from the complaint before it went to trial.

The city was ordered to pay Volletta Wallace, who along with Combs served as a producer on the 2009 biopic Notorious, $1.1 million in sanctions. Her original suit, filed in 2002, ended in a mistrial in 2005; she refiled in 2006 but agreed to withdraw the suit in 2010. The task force was subsequently disbanded.

“What bothers me the most about these cases is the paradox, you know—all the mysteries, and theories and conspiracies, the conspiratorial thinking that surrounds them—when in fact the answers to these two murders are relatively simple, they’re quite straight forward and direct,” Kading told E! News. “It doesn’t make any sense. If that’s the truth, then why hasn’t anybody been brought to justice? Well, we didn’t figure this stuff out until long after the fact. Unfortunately law enforcement back in 1996 and 1997 just weren’t able to get what they needed to solve the cases. And that’s frustrating.”

“That’s all the justice that these cases will see,” Kading also told Complex in 2012. “The co-conspirators are never going to be prosecuted. Unfortunately, the cases are so complicated and convoluted. These will never see criminal prosecution.

“The co-conspirators are absolutely known and I say that with conviction. I worked directly on these cases for years and know exactly where they stand within law enforcement. They would be very problematic prosecutions because of all of the convoluted peripheral issues that were raised during the investigation. The D.A. in Los Angeles knows that this is an extremely difficult situation to try and prosecute. Here’s the problem: You’ve got [Suge’s girlfriend] confessing, and then, there was a bad move by law enforcement to give her immunity. The shooter’s dead, the female confessor has immunity, so you just have Suge Knight.”

Knight, who’s never been charged with anything related to Wallace’s or Shakur’s death, is currently in prison. The now 54-year-old Death Row Records co-founder was sentenced to 28 years in October after pleading no contest to manslaughter for hitting two men with his truck outside a Compton burger stand, killing one and seriously injuring the other, after an argument during filming on 2015’s Straight Outta Compton.

He originally claimed he acted in self-defense.

Kading also disputed Russell Poole’s theory of the case, that dirty cops were involved, which he arrived at with the help of a jailhouse informant who named, vaguely, someone named Amir as the possible shooter in Biggie’s case.

“Coincidentally, [David] Mack has a friend named Amir Muhammad,” Kading told Complex. “That circumstantial connection, put this investigator [Poole] down a rabbit hole.”

He said, “There was all this exaggeration of information, and a whole theory was built on it, which never had a basis but captured the popular imagination. Actually, the individual who brought that information to the L.A.P.D. recanted and said, ‘I made it all up. It was all bulls–t.'”

Poole died of a heart attack in 2015. Randall Sullivan‘s 2002 book LAbyrinth details the various roadblocks Poole came up against within the LAPD during his investigation. City of Lies, the movie starring Johnny Depp as Poole and Forest Whitaker as a journalist following the case, was slated for a Sept. 7, 2018, release but Global Road Entertainment pulled it from the schedule.

Sullivan’s follow-up book, Dead Wrong: The Continuing Story of City of Lies, Corruption and Cover-Up in the Notorious B.I.G Murder Investigation, comes out Monday.

“Russell Poole…obsessed about this until he died, right up until it basically might have been the reason he died,” Josh Duhamel told E! News last year. “My character [Greg Kading] started to go down that same path, and really truly wanted to bring justice to Christopher Wallace’s mother. He was hired to find out what happened.

“He knew what happened, but wasn’t able to prove it. It’s not what you know, it’s what you can prove, and that’s really what the tragic part of this is, is that real justice was never brought to these families.”

(E! and USA are both members of the NBCUniversal family.)

(This story was originally published on Feb. 25, 2018, at 6 a.m. PT)