Getty Images; AP; Melissa Herwitt / E! Illustration

Show us a sport and we’ll show you a scandal.

There is no such thing as competition without controversy, and when you add millions of dollars; massive egos; years of blood, sweat and tears; and international tension, sometimes between countries that don’t much like each other even on a good day, you’ve got controversy on steroids.

Sometimes literally.

And though it’s beautiful to look at and the inevitable stories of triumphing over adversity are heartwarming, figure skating has had its share of issues.

Surely by now the memo has been circulated advising all up-and-comers (and their supporters) that sabotage doesn’t pay. So, it was all the more surprising when a complaint was lodged against U.S. skater Mariah Bell by Korean skater Lim Eun-soo‘s management team, which claimed Bell intentionally slashed Lim’s leg with with the blade of her skate during a practice session March 20 at the ISU World Figure Skating Championships in Saitama, Japan.

All that Sports alleged that Bell “suddenly kicked and stabbed Lim’s calf with her skate blade” and didn’t apologize, but the International Skating Union, after meeting with U.S. and Korean delegates and reviewing video footage, determined that there was no evidence that Bell intended to hurt Lim.

“This article is click bait. I’ve been to the rink multiple times and NO ONE has been bullying anyone,” U.S. skater Adam Rippon, a bronze medalist for the U.S. in the team event at the 2018 Olympics, tweeted in reaction to the accusation against Bell. “Stop creating s–t and spreading rumors. What happened in the warm up was an accident. Don’t distract both Eunsoo and Mariah from the competition.”

Koki Nagahama/Getty Images; Matthew Stockman – International Skating Union (ISU)/ISU via Getty Images

That was not the end of it on Twitter, however, where the debate continues on behalf of both Bell, 22, and Lim, 16, who finished sixth and fifth, respectively, in the short program, with the free skate to come Friday.

Social media certainly adds an extra layer these days to any incident, no matter how big or small, real or imagined, and it’s exhausting to think how low the discourse would have devolved in, say, 1994.

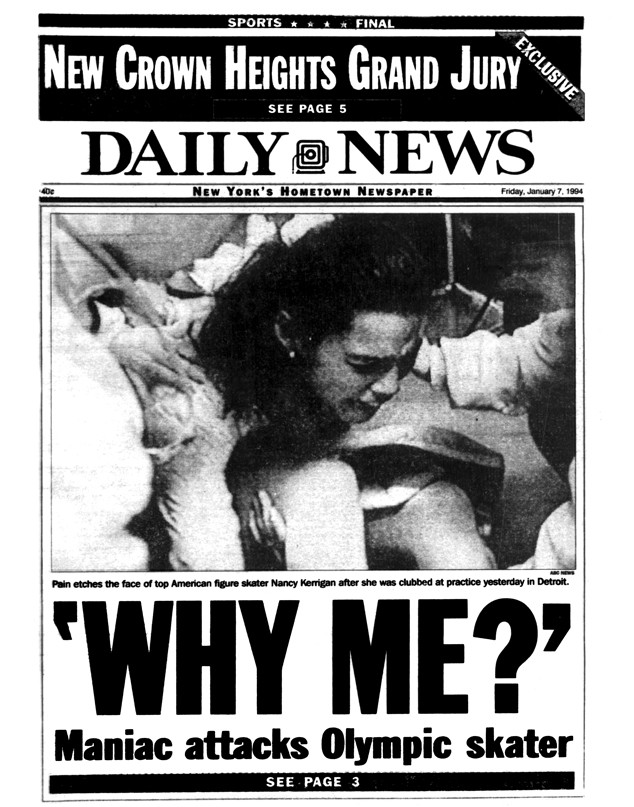

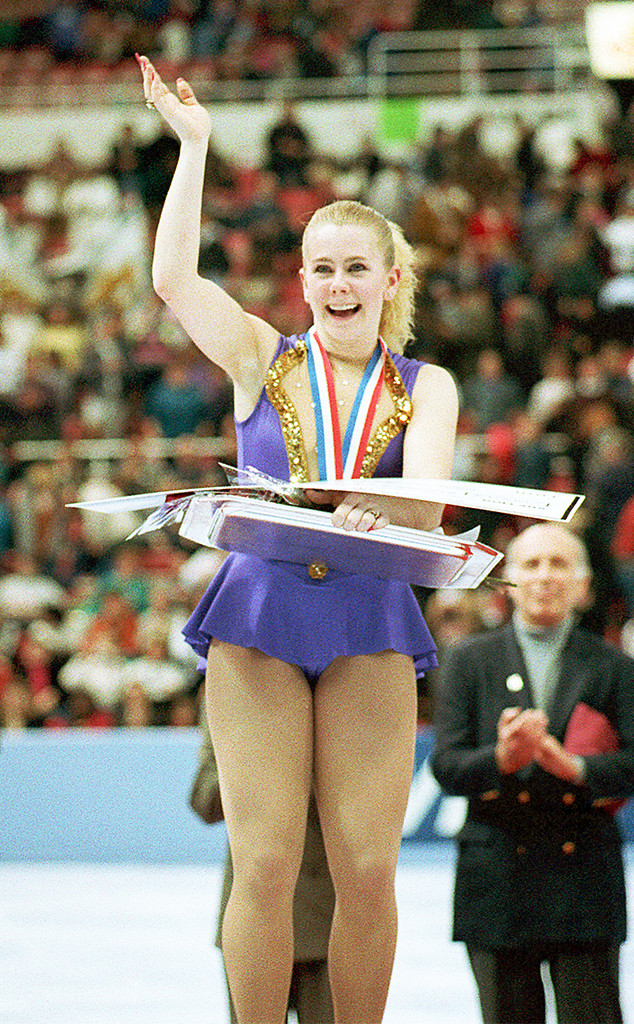

The release of I, Tonya and Allison Janney‘s subsequent awards-season sweep in 2018 resurfaced the story of Nancy Kerrigan getting whacked on the knee in an otherwise hapless attack arranged by Tonya Harding‘s ex-husband Jeff Gillooly 25 years ago—and shed fresh perspective on how quickly the lines were drawn in the ice.

NY Daily News via Getty Images

Kerrigan was traumatized but physically OK enough to win a silver medal a month and a half later at the 1994 Winter Olympics in Lillehammer, where Harding finished eighth after having a meltdown over a broken skate lace.

Gillooly spent six months in prison after pleading guilty to racketeering for his role in what proved to be a career-killing PR debacle for Harding. The athlete herself pleaded guilty to hindering prosecution in March 1994, though it was only last year that she admitted to figuring out what had happened after the fact but didn’t tell authorities. She was banned for life from the United States Figure Skating Association and stripped of the national title she won two days after Kerrigan was attacked.

“You are a prime example of how ruthless ambition and raw greed can disrupt, degrade and disfigure a sport of grace even to the height of the Olympics,” Circuit Judge Donald Londer told Gillooly at sentencing. “All that will be recalled is a band of thugs from Portland, Ore., tried to rig the national figure skating association championships and the Olympics by stealth and violence.”

As I, Tonya intended, it’s impossible to watch the film and not come away with the sinking feeling that Harding was competing against the odds all her life and was more of an innocent bystander in her own rather tragic story than the villain the tabloids made her out to be in the mid-’90s.

AP Photo/Lennox McLendon

“I knew that this would be with me for the rest of my life,” Harding told the New York Times—and she wasn’t talking about the fact that she was the first American woman to land a triple axel in competition.

She also admitted that the public perception of her (wild remembrances of the incident have ranged from people thinking she personally arranged the attack to thinking she clubbed Kerrigan herself) still got to her sometimes.

“I do care. I mean, I care, but I don’t care,” Harding told ABC News in December 2017. “The most important people are my family and my closest friends. Everybody else’s opinions don’t matter. So my motto is, ‘Take care of me, so I can take care of my family.'” She recalled, “The media had me convicted of doing something wrong before I had even done anything at all, before I had talked to anyone, before I get out of bed. I’m always the bad person.”

While that act of violence in the name of competition turned out to be an isolated event in figure skating, a different kind of controversy emerged in its wake.

TIMOTHY A. CLARY/AFP/Getty Images

Eight years later in Salt Lake City, the pairs figure-skating competition at the 2002 Winter Olympics was allegedly fixed—you know, no big deal—and the debacle prompted an overhaul of the age-old scoring system.

Which in turn, according to critics, made the scoring even more incomprehensible. Gone was the old way where skaters were judged out of 6 on technical merit and artistry, and in came different possible high scores for each skater based on the difficulty of the tricks they planned to execute and how well they did so, plus overall presentation.

“Of course, the drama of a perfect mark has been taken away, but things had to evolve,” Canadian figure skater David Pelletier told CBC Sports in January 2018. “People watch figure skating for the athleticism and emotion that it can bring more than for the marks the athletes can receive.”

JACQUES DEMARTHON/AFP/Getty Images

It was Pelletier and partner Jamie Salé (the couple married in 2005 and have a son together) who were at the center of the controversy in 2002 after they were awarded the silver medal behind Russian pair Elena Berezhnaya and Anton Sikharulidze—which didn’t appear right to anyone who had just watched Pelletier and Salé skate.

Amid the uproar, French judge Marie-Reine Le Gougne tearfully admitted to throwing her vote to the Russians in exchange for a Russian judge’s vote for a French ice-dancing pair, after being pressured from the president of the French Ice Sports Federation, Didier Gailhaguet, to do so. Gailhaguet thoroughly denied exerting any pressure on LeGougne. (He resigned in 2004—and then was reelected in 2007.)

Le Gougne then recanted her confession, saying she’d been under pressure yet again, this time by the International Skating Union, to admit to something she didn’t do. After being suspended indefinitely, she told the French paper L’Equipe that she really did think the Russians should have won in the first place and she voted accordingly. “I judged in my soul and conscience,” she said. “I considered that the Russians were the best. I never made a deal with an official or a Russian judge.”

Le Gougne then accused ISU technical committee chairwoman Sally Stapleford, who was British but also had a Canadian passport because her father was Canadian, of masterminding a plot to put Canada on top by drumming up a French conspiracy. Attorney and ISU championship judge Jon Jackson told a reporter at the time, “When accusations get that ridiculous, it’s an indication that people are running scared.”

MENAHEM KAHANA/AFP/Getty Images

Pelletier and Salé were ultimately awarded gold medals (at a ceremony that the Russian pair, who got to keep their medals as well, gracefully attended) and Le Gougne wrote a tell-all book, Glissades à Salt Lake City. And now no one understands how figure skating is scored.

The grumbling over skating’s scoring system never abated, with many befuddled athletes, fans and entire countries more united in their annoyance than ever.

YURI KADOBNOV/AFP/Getty Images

When the medals were handed out in Sochi in 2014, more than 2 million people signed a Change.org petition demanding an investigation into the judging of the women’s figure skating after Russian Adelina Sotnikova won the gold over South Korea’s Yuna Kim, who won gold in Vancouver 2010 and retired after the Sochi Games.

It was the first women’s figure-skating gold for Russia and Sotnikova’s best finish in non-junior international competition. She wasn’t even the favorite from her own team to win gold, those hopes having been placed on 15-year-old Julia Lipnitskaia. You’d think the underdog, out-of-nowhere angle would’ve worked for people. Instead, however, critics of the scoring system and the judges implementing it were irate that Sotnikova skated away with the gold after attempting just enough trickery to win and turning in a tidy, though not perfect performance. (Most of the online angst came from people in Korea.)

“I am stunned by this result, I don’t understand the scoring,” Katarina Witt, who won back to back individual golds (in 1984 and 1988, for East Germany), reportedly said on German TV.

Hers is definitely more of a traditional perspective, one shared by many but which doesn’t serve any athlete, coach or analyst to harp on these days. (And speaking of traditional, even U.S. champ Dick Button, who won men’s figure skating gold at the Olympics in 1948 and 1952, weighed in via Twitter: “Sotnikova was energetic, strong, commendable, but not a complete skater. I fear I will never be allowed back in Russia again.”)

“Adelina collected more points,” said 1984 Olympic gold medalist turned TV commentator Scott Hamilton, who was watching from the NBC booth. “That is really the only way you can describe it. If you look at Yuna of the past, this was not a program as difficult as she has done, and she left the opportunity for someone to collect points on that side of the scoring. It may not have been as beautiful as Yuna and Carolina, but under the rules and the way it works, she did all that…I think it was a just strategy that worked on the night.”

Ultimately, there was no official protest filed with the ISU or International Olympic Committee, so no official investigation was conducted. However, the Chicago Tribune pointed out that one of the judges on the panel was married to the general director of the Russian Figure Skating Association, and another judge, from Ukraine, had actually been banned from judging for a year after getting caught in a result-fixing plot in 1998.

Meanwhile, does anyone else think the current athletic-proficiency-over-artistry approach might have served someone named Tonya Harding back in the day?

Matthew Stockman/Getty Images

In the aftermath of Sochi, in 2016 the International Skating Union ended judging anonymity, which had been implemented in response to the uproar in 2002—a welcome change for those clamoring for more transparency in the sport, not less.

Fast-forward to this year at the U.S. National Championships (all roads lead to the Olympics in this sport) and Ashley Wagner, who was a member of the group that won bronze in the inaugural team competition in Sochi but missed out on making the team that went to Pyeongchang.

Aside from her Sochi teammate Gracie Gold, who took herself out of the running for a 2018 Olympics spot last fall to focus on her physical and mental health, Wagner is the United States’ most well-known star on the ice—so call a country confused that the judges poked so many holes in her performance.

That’s right, in a sport where the national bias is now just assumed, Wagner didn’t even benefit from her own home-soil advantage. She finished fourth at nationals and champion Bradie Tennell, silver medalist Mirai Nagasu and bronze medalist Karen Chen went on to compete in the 2018 Winter Olympics.

“I’m furious, I am absolutely furious,” Wagner told reporters afterward. “I know when I go and I lay it down and I absolutely left one jump on the table, but for me to put out two programs that I did at this competition as solid as I skated and to get those scores, I am furious, and I think deservedly so.”

In an attempt to avoid a deduction for poor sportsmanship in the court of public opinion, she tweeted later, “As an athlete, I’m allowed to be mad. As a senior competitor with over 10 years of experience, I’m allowed to question things. At the end of the day, I laid out my best and I’m going home proud! Congrats to the lovely ladies of the team, you’ve got me in your cheering squad now! Lastly Twitter, before you eat me alive, don’t forget there is a real person on the other end of your tweets.”

The 26-year-old, whose competitive Olympic career is effectively finished, said on Today a few days later that she didn’t regret reacting strongly in the moment.

“I think the only thing that I question is my scores compared to my scores in the past,” she continued. “I scored lower in the second mark in my short program than I did in a competition that I was injured at and those are the things that I’m confused about, but you know, the technical side, I think was totally fair and I ended up where I ended up, but, I mean, that moment I created for myself—a standing ovation at Nationals, that’s something that for me, I’ll forever be proud of.”

And if she had made the U.S. team, she still would have skated right into a hotbed of national subjectivity and playing favorites. (Which she presumably remembers from 2014, having had one of the more meme-able reactions when she saw her short-program scores in Sochi, where she finished seventh overall in the individual competition.)

Darren Cummings/Pool/Getty Images

Which is apparently just the way it is. An analysis from BuzzFeed News found that 16 of the 48 figure-skating judges who were headed to Pyeongchang—including two each from Canada and the United States, three from China and all three Russians—had evinced a pattern of showing preference to skaters from their own countries in international competition. And a single judge inclined to give a boost to his or her country’s team could influence the medal standings if the scores are close enough.

NBC News noted, as well, that 33 of the 164 judges considered eligible to judge the skating this year hold or once held leadership positions with their national skating federations—and 11 of the aforementioned 48 fit that bill, including a Korean judge who told a newspaper that she would make sure skaters from her country were “not disadvantaged” this year.

And speaking of scandal, all 163 Russian athletes at the Olympics in Pyeongchang, including 15 figure skaters, competed as “Olympic Athletes From Russia,” due to the ban slapped on their national team for what the IOC determined was an entrenched, widespread, allegedly government-sanctioned doping program.

Meanwhile, despite all the talk of favoritism, there is such a thing as the exact opposite of support from one’s home country in skating—but that appears to be reserved for those who really upset their compatriots.

Schirner Sportfoto/picture-alliance/dpa/AP Images

Norwegian figure-skating legend Sonja Henie, who though she later became a U.S. citizen and made an anti-Nazi film when she turned to acting, was a personal favorite of Adolf Hitler‘s when she was in her skating prime.

Henie won back-to-back-to-back individual figure-skating gold medals at the 1928, 1932 and 1936 Olympics (the last of which was held in Berlin but is not to be confused with the 1936 Summer Olympics, which is most remembered for U.S. track star Jesse Owens‘ four-gold-medal performance under Hitler’s maniacal gaze), but not before causing widespread outrage back in Norway.

In Berlin before the Olympics, Hitler and his entourage came to watch her skate and she greeted him with the Nazi salute and a “heil Hitler,” prompting headlines speculating that she was some sort of Nazi or Nazi sympathizer. (The general consensus, however weak, was that she was just going with the flow and was not a political person.) She did not repeat the gesture during the Olympics, but Hitler presented her with an autographed photo along with her gold medal, after which she and her parents are said to have accepted an invitation to lunch with him.

“I don’t think Sonja Henie was a political person in any way, shape, or form,” Dick Button told Vanity Fair in 2014. “She was an opportunist… I don’t think she could have cared less who Hitler was, except for whatever power he had and what it would do for her career.”

The 1940 and 1944 Winter Olympics—to be hosted by Japan and Italy, respectively—were canceled due to World War II. After the 1936 Olympics, Henie retired from skating and set her sights on Hollywood, marrying an American (her first of three husbands) and becoming a naturalized citizen in 1940. She ultimately supported U.S. war efforts, but it didn’t escape notice that she didn’t donate to the Norwegian resistance until after Pearl Harbor.

Still, she received a warm welcome when she returned to Norway on a skating tour of Europe in the summer of 1953, 33 performances to sold-out crowds.

“It was like, My God, she’s here, she’s alive,” remembered Don Watson, a skating protegee and longtime friend of Henie, in Vanity Fair. “Beautiful figure, costume, lighting. Some of the Norwegians had to come back twice. The majority of the audience stood. Seven thousand people standing.”

(Originally published Feb. 10, 2018, at 6 a.m. PT)