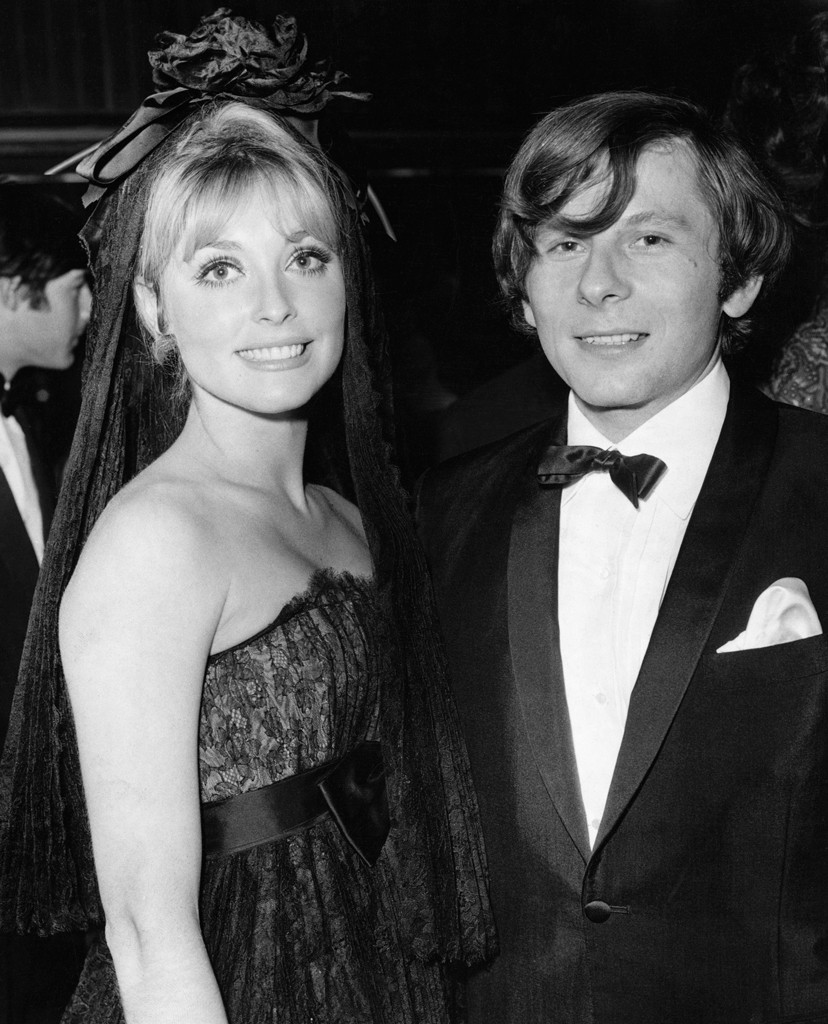

Globe Photos/Shutterstock

“I don’t like that word starlet at all, because there’s no such thing actually. I feel, at least in my estimation, that every person, if they want to be an actress or they want to stay in the acting world—which is a pretty tough world—before you even make an appearance, it’s very necessary to learn your craft first, and take as much time, and do as much as you can.”

So said Sharon Tate in 1966, when she was an unarguably stunning up-and-comer who came to Hollywood with big dreams, which she hoped were on the verge of panning out.

Three years later, she was a legend.

The actress had a handful of B-movies, most memorably Valley of the Dolls, and some TV guest spots to her name when, at 26 years old, she was one of seven people murdered by members of Charles Manson‘s so-called “family” over the course of two nights of carnage that shook Hollywood and made Tate more famous than anyone’s wildest ambitions could have anticipated.

Fifty years later, Tate remains frozen in time, the accidental co-star of one of the most gripping, gruesome and parsed-over crime dramas to worm its way into the fabric of our culture. Her story has often been a footnote to Manson’s, however, her life a casualty all over again when weighed against the still literally insane details of what he and his followers did.

Lindsay Lohan made a well-meaning but not well-received attempt to draw attention to Tate in 2015, dressing up in a mod, ’60s-style outfit reminiscent of the actress’ hey-day. “I LOVE SHARON TATE,” she wrote amid myriad hashtags on Instagram. It’s unclear if she knew it was also Manson’s 81st birthday that day, but the many commenters who found it disrespectful didn’t care either way.

Yet she wasn’t wrong that Tate posthumously became a style icon in addition to a retroactively appreciated actress, to forever be remembered for what could have been.

And with Tate being portrayed three times on the big screen in 2019 alone—by Hilary Duff in Daniel Farrands‘ The Haunting of Sharon Tate, Grace Van Dien in Mary Harron‘s Charlie Says and Margot Robbiein Quentin Tarantino‘s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood—there’s no time like the present to put Tate back at the center of her story, a true tale that bucks the conventions of reality at every turn.

Globe Photos Inc/REX/Shutterstock; Andrew Cooper/Sony Pictures

There has been no cease in the telling and retelling of Manson’s story, how the diminutive musician from Ohio got people to kill for him and how he held sway over countless others.

No true crime renaissance was needed to bring the interest in that back. The focus on bad people and the terrible things they’ve done has yet to go out of fashion. But at least there’s room in this sprawling storytelling landscape of ours to remember the lives that actually deserve remembering.

“In 1969 my sister was involved in an event that changed the country in ways that still resonate,” her sister Debra Tate wrote in the introduction to the 2014 book Sharon Tate Recollection, featuring dozens of photos of the late star. “That said, I always felt it was very unfair for her life to be remembered primarily for its final moments. Sharon had a magnificent life.”

There were a few more months to go, but the events of the early morning hours of Aug. 9 and Aug. 10, 1969—which came to be referred to in homicide parlance as the Tate-LaBianca murders—effectively ended the 1960s. For Sharon Tate, it had been the decade in which everything had happened.

The eldest of Col. Paul Tate and Doris Tate‘s three daughters, Sharon was born in Texas—at 6 months old she was crowned Miss Tiny Tot of Dallas after her grandma submitted photos of her—but the family moved around a bunch as dictated by Paul’s Army career. At 16, she was Miss Richland, Washington, then Queen of the Autorama at a car show. She moved to Verona, Italy, with her parents and sisters Debra and Patricia in 1960.

She went to an American high school, where she was a cheerleader and prom queen in 1961. According to a shockingly brief mention in Ed Sanders’ 2016 biography Sharon Tate: A Life, Tate told Roman Polanski on their first date that she was raped by a soldier in Italy when she was 17, but as Polanski put it, she said the attack “‘hadn’t left her emotionally scarred.'”

Knowing already that acting was for her, she would seek out the sets of film shoots in the area, and she ended up an extra in the swords-and-sandals epic Barabbas. Her mother allowed one of the film’s stars, Jack Palance, to take her out on a dinner date. Gossip columnist Hedda Hopper also linked a 19-year-old Tate to Richard Beymer, who had just filmed the role of Tony in West Side Story and was shooting Adventures of a Young Man in Verona.

In the summer of 1961, Tate’s father was assigned to San Pedro, Calif. She beat her parents to Southern California by a few months to get a head start on her aspirations.

“You must remember,” she told interviewer Robert Musel a few years later, “that I was shy and bashful when I reached Hollywood. My parents were very strict with me. I didn’t smoke or anything. I only had just enough money to get by and I hitchhiked a ride on a truck to the office of an agent whose name I had. That very first day he sent me to the cigarette commercial job. A girl showed me how it should be done, you know taking a deep, deep breath and look ecstatic.”

Eventually she passed out from too many puffs. “That ended my career in cigarette commercials,” she laughed.

When Tate was 20, she auditioned for what become Petticoat Junction, and was brought to the attention of Martin Ransohoff, executive producer of The Beverly Hillbillies. He and partner John Calley signed Tate to a seven-year contract. Tate recalled him actually saying to her, “‘Baby, we’re going to make you a star.'”

Her agent negotiated a salary of $750 a month for her and she moved into the all-women Hollywood Studio Club, the onetime home of Marilyn Monroe, Kim Novak, Rita Moreno and many more familiar names.

In 1963, according to what Tate’s mother would later tell police about their daughter’s life, she had been involved with a French actor who at one point beat her up so badly she needed to go to the hospital. Ed Sanders writes about Tate’s relationship with Philippe Forquet, whom she lived with in New York while briefly studying acting with Lee Strasberg. They returned to L.A. supposedly engaged, though there was some doubt that they were that serious, that it wasn’t the studio system at work whipping up publicity. After reports surfaced that he put her in the hospital, Forquet said that Tate cut him in the chest with a broken wine bottle.

In 1964 she met hairstylist Jay Sebring, who had recently separated from his wife. He and Tate dated, and eventually lived together, until she fell for Roman Polanski when he directed her in The Fearless Vampire Killers.

While she was being groomed for bigger things, Ransohoff would have his new future star wear a black wig (so she wouldn’t be recognized yet) and appear in a bit role on The Beverly Hillsbillies to get her used to being on camera. In the old-school studio system, it was common for promising talent to basically sign away their professional (and oftentimes personal) lives to the studio or production company, in exchange for the promise of a career.

By the 1960s, it wasn’t as common, but that was the experience Tate was having. In fact, without her having done anything particularly noteworthy onscreen yet, European papers were calling her the next Marilyn Monroe.

Ezio Praturlon/Shutterstock

“Well, it’s very strenuous, I must say,” Tate said in a 1966 interview when asked what the process had been like for her. “For approximately three years, I’ve had no personal life, I guess you could call it. I’ve done nothing but study from 8 o’clock in the morning till about 6:30 at night. Then on three evenings out of every week I went to a night class, too.

“I had acting classes, voice, singing, body building—everything, absolutely everything. Which is necessary, you know.”

Asked by the interviewer if, having been toiling away like that, she felt like a “prisoner” of the system, Tate said no.

“Never, not really,” she replied. “I felt that, if you’re serious about it, it’s a lot of hard work. If not, you play and you get absolutely nowhere at all.”

She laughed heartily at the Marilyn comparisons. “Oh, dear,” she shook her head. “I love Marilyn Monroe, but it would be kind of difficult for me to be another Marilyn Monroe, I think.” Asked if she saw herself being subjected to similar pressures as the late star, who had died in 1962, Tate replied again, “Oh, dear. In my estimation that kind of a sex symbol is really gone. It’s more imagination. Sexiness to me is part of every movement. You don’t see the big low-cut dresses anymore, it’s more all to the imagination.”

Mgm/Kobal/Shutterstock

Until then her film work consisted of commercials and uncredited roles, such as “Beautiful Girl” in The Americanization of Emily, which Ransohoff produced, that seemingly ended up on the cutting room floor. She and the black wig had been on 15 episodes of The Beverly Hillbillies and she had appeared on The Man From U.N.C.L.E. and Mr. Ed. One of her most enriching experiences had come when she went to Big Sur to shoot a bit role in The Sandpiper with Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, and she loved the coastal enclave so much it’s where she would return time and again to decompress.

But the world was about to meet Sharon Tate—the earnest, dedicated, blond Sharon Tate.

She appeared in four movies that came out in 1967, three Ransohoff-produced films—Eye of the Devil, Don’t Make Waves and the horror spoof The Fearless Vampire Killers—and the coup de gras, Valley of the Dolls, adapted in rapid fashion from Jacqueline Susann‘s best-selling 1966 novel that also made the author an overnight sensation.

20th Century Fox/Kobal/Shutterstock

As Tate was being interviewed aboard the Princess Italia after the film’s world premiere as the yacht sailed from Italy to California as part of a splashy promotional campaign, she was the big breakout star of the moment. She was nominated for a Golden Globe in 1968, Most Promising Newcomer (she lost to The Graduate star Katharine Ross) and quickly booked two more films, The Wrecking Crew and 12+1, featuring wildly different co-stars in Dean Martin and Orson Welles.

She also got married.

Tate first met Roman Polanski in 1966 when she was in London filming Eye of the Devil. The Oscar-nominated filmmaker, born in Paris and raised in Poland, where he lost his mother in the Holocaust, was coming off the critical and commercial success of his first English-language film, the 1965 psychological thriller Repulsion starring Catherine Deneuve. He had already made a name for himself in Europe—as a visionary and a playboy.

Polanski had been married before, to Polish actress Barbara Kwiatkowska-Lass, and he showed no signs of wanting to settle down again, even as he pursued Tate throughout the filming of The Fearless Vampire Killers. He also photographed her semi-nude for Playboy during the shoot.

When Sebring went to visit Tate in London after they wrapped, she told him she had fallen in love with Polanski, which he seemed to accept, though friends suspected he still harbored feelings for the actress.

At the same, heartbreak didn’t hurt his dating life, and he is said to have been the inspiration for Warren Beatty‘s playboy hairdresser in Shampoo.

When they first met, “I thought she was quite pretty, but I wasn’t at that time very impressed,” Polanski later told detectives at Parker Center, headquarters of the Los Angeles Police Department, after his wife was killed. “But then I saw her again. I took her out. We talked a lot, you know. At that time I was really swinging. All I was interested in was to f–k a girl and move on.”

He didn’t start sleeping with Tate, he said, until a few months into shooting The Fearless Vampire Killers. “She was so sweet and so lovely that I didn’t believe it, you know,” he marveled to police. “I’d had bad experiences and I didn’t believe people like that existed.”

While waiting for the other shoe to drop, he realized that Tate was as good of a person as she seemed. “She was fantastic,” he recalled. “She loved me.” And she gave him the space that, despite being enamored with her, he apparently still needed.

“I said, ‘You know how I am; I screw around.’ And she said, ‘I don’t want to change you.’ She was ready to do everything, just to be with me. She was a f–king angel. She was a unique character, who I’ll never meet again in my life.”

As far as the spurned Jay Sebring was concerned, Polanski said, “I’m sure in the beginning of our relationship there was still his love for Sharon, but I think that largely it disappeared. I’m quite sure.”

Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

When Polanski and Tate married in London on Jan. 20, 1968, he was about to have a hit on his hands with Rosemary’s Baby, his adaptation of Ira Levin‘s book, the biggest-selling horror novel of the 1960s, starring Mia Farrow, John Cassavetes and Ruth Gordon, who’d win a Supporting Actress Oscar for her turn as the neighbor from hell.

The film premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in May 1968, and there are photographs of Tate living it up with her husband, Farrow and assorted other jet-setters.

Meanwhile, Tate is said to have asked Ransohoff to let her out of her contract not long after the Princess Italia docked, saying she wanted to be a full-time wife and, eventually, mother—but her Golden Globe nomination, the success of Rosemary’s Baby and more exciting happenings prevented her from pressing the issue.

Mgm/Filmways/Kobal/Shutterstock

By the time she got pregnant at the end of 1968, there was already speculation that Tate was hanging all her hopes of saving her marriage upon the baby. Some of their friends said she waited to tell Polanski she was pregnant until it was too late for her to have an abortion.

“I guess I kind of live in a fairy tale world,” she’s quoted in Restless Souls, by Alisa Statman and Sharon’s niece Brie Tate, one of her sister Patti’s daughters. “We have a good arrangement; Roman lies and I pretend to believe him.”

At the same time, when they had a chance to nest together in L.A. (she convinced him to at least rent a home, resisting his excuse that he liked being able to pack up and leave a place anytime he wanted) they were happy. After a bungalow at Chateau Marmont proved not to be the kind of home base she had in mind, they spent several months renting her Valley of the Dolls co-star Patty Duke‘s house.

In early 1969, Tate and Polanski rented 10050 Cielo Drive, nestled off of Benedict Canyon by the upscale neighborhood of Bel Air, over the phone from its outgoing tenant, record producer Terry Melcher. The home’s owner, Rudy Altobelli, hired a live-in caretaker named William Garretson to look after the property. Garretson lived in the guest house behind the gated main residence, a sprawling French country-style home.

It seemed entirely inconsequential at the time, but Melcher had recently been unimpressed by the music of aspiring singer-songwriter Charles Manson, whom he’d met through Beach Boy Dennis Wilson, who met Charlie after picking up some hitchhiking female members of the “family.” Melcher later remembered Manson being in the car one night when Wilson gave him a ride home when he was living at Cielo Drive.

Tate, who was filming 12+1, and Polanski were in Europe that March when their friends Abigail Folger, an heiress to the Folger coffee fortune, and her boyfriend Voytek Frykowski moved in. Tate returned alone from Europe in July via ocean-liner because she was too far along in her pregnancy to fly, and the couple planned to stay in the house with her until Polanski returned for the birth of their baby.

On the night of Aug. 8, the three of them went out to El Coyote Cafe, a Mexican restaurant on Beverly Boulevard that remains open to this day, with Sebring, who had remained a friend of Tate and her family, including her husband and her parents.

They all went back to the house on Cielo Drive after dinner. Folger was supposed to fly up to San Francisco the next morning to see her mother.

Housekeeper Winifred Chapman found the bodies the next morning—all four friends and 18-year-old Steven Parent, an acquaintance of Garretson who had just driven up to the house when Charles “Tex” Watson, Susan Atkins, Patricia Krenwinkel and Linda Kasabian (the prosecution’s eventual star witness) arrived. Parent, who worked part-time at a stereo shop and was there to see if Garretson wanted to buy some equipment, was shot dead in his Rambler. Garretson would briefly be a suspect, because he was alive and well and in the guest house when police arrived on the scene.

Authorities contacted Polanski’s friend and business manager, William Tennant, who was on the tennis court when he got the call, and he went to the house and identified Tate, Frykowski, Folger and Sebring, but had no idea who the young man in the car was.

He was the one to call Polanski, who was in London finishing production on The Day of the Dolphin.

As relayed in Vincent Bugliosi‘s Helter Skelter, the definitive book on the murders, Tennant said, “Roman, there’s been a disaster in a house…Your house. Sharon is dead, and Voytek and Gibby and Jay.” The filmmaker was in disbelief and asked how it had happened. He thought perhaps a fire. Not a massacre.

Tate, who was 8 months pregnant, was in a floral-printed bra and matching underpants when she was stabbed 16 times, five of them wounds that would have been fatal on each of their own. A rope was looped around her neck, strung over a rafter above and the other end was wrapped twice around Sebring’s neck. Atkins wrote “pig” on the front door in Tate’s blood.

Sebring, whose real name was Thomas John Kummer, had been living in another Benedict Canyon home, on Easton Drive, that had once belonged to actress Jean Harlow, who died at 26 due to complications of kidney failure (which has been attributed via conspiracy theory to everything from hair dye poisoning to a botched abortion). More eerily, Harlow’s husband, producer Paul Bern, committed suicide in her bedroom two months after they got married.

People who knew Sebring told Bugliosi he had bought the house because of its “far out” reputation. He owned a salon on Fairfax Avenue in L.A. and had just opened a shop in San Francisco in May 1969, step one in his plan to open numerous locations and launch a line of men’s grooming products. He was stabbed seven times and shot once.

Folger was a debutante and Radcliffe graduate who had driven from New York to L.A. with Frykowski, a twice-married father of one, whom she met in 1968. He was a friend of Polanski’s from Poland; his father had financed one of Polanski’s early films and Voytek played a thief in his short film Mammals. That’s how Folger met Tate and Sebring, even investing in the burgeoning Sebring International. She was a volunteer social worker for the L.A. County Welfare Department up until the day before she and Frykowski moved into 10050 Cielo Drive.

Depressed and disillusioned by all the suffering she had seen in the course of her work, and using a lot of drugs iwth Frykowski, she apparently told her psychiatrist—whom she saw every weekday afternoon—on Friday, Aug. 8 that she was thinking of breaking up with her boyfriend.

While processing the crime scene, authorities found 6.9 grams of marijuana in a baggie in a living room cabinet. There were 30 grams of hashish in the nightstand in the bedroom where Frykowski and Folger were staying, along with 10 pills that turned out to be amphetamines—all of which served to fuel wild speculation that the murders were the result of a drug deal gone wrong, or that someone had freaked out during a drug-fueled bacchanal.

Folger, who was stabbed 28 times, had 2.4 mg. of MDA in her system, while Frykowski had .6 mg. in his.

Voytek would tell people he was a writer, but mainly he had ideas about what to do next. “He had no means of support and lived off Folger’s fortune,” investigators noted in their report, but he was apparently the life of many a drug party. He was shot twice, struck in the head 13 times and stabbed 51 times.

Polanski later told police that his wife had used LSD over a dozen times, mostly before they met, but otherwise did nothing but smoke pot. “And during her pregnancy there was no question,” he said. “She was so in love with her pregnancy she would do nothing. I’d pour a glass of wine and she wouldn’t touch it.”

Asked later why they went to that particular house that night, Susan Atkins recalled to authorities that Tex told them they were “going to a house up on the hill that used to belong to Terry Melcher, and the only reason why we were going to that house was because Tex knew the outline of the house.”

Their mission once they got there: “To get all of their money and to kill whoever was there.” It didn’t matter who was there.

When Polanski arrived in L.A., he was immediately bombarded with questions about his rumored marital troubles. He insisted he had only stayed behind in London to work on his movie, that he was planning to be in L.A. for the birth of his first child.

The funeral for Sharon Tate and their unborn baby, Paul Richard Polanski, was held on Aug. 13 at Holy Cross Cemetery.

More than 150 people came, including Warren Beatty, Kirk Douglas, Steve McQueen, Peter Sellers and John and Michelle Phillips of the Mamas and the Papas. Mia Farrow was said to be too distraught to go to the service—numerous celebrities were reportedly terrified, wondering if the killings would continue and famous people would be targeted. McQueen started keeping a gun under the front seat of his car.

Sebring was laid to rest at Forest Lawn, with many of the same mourners in attendance, as well as other clients and friends such as Paul Newman and Henry and Peter Fonda.

There was no internet to fan the flames, but rumors still spread like wildfire in the early days of the investigation, before law enforcement announced in December that they had the people were responsible for the Tate murders, as well as the similarly brutal Aug. 10 murders of Leno and Rosemary LaBianca, in custody.

Jumpers of the gun started connecting phantom dots between the dark themes and violence (though mainly implied) found in Polanski’s films and the ritualistic aspects of the murders. There was speculation that Tate and her pals were devil worshipers, or they had been having some sort of orgy that went wrong, or at the very least Tate had been having sex with Sebring, her old boyfriend. False information about the nature of the wounds and the positions the victims were found in made the rounds. Polanski allowed a photographer from Life magazine to accompany him when he returned to the house for the first time, which struck some as a rather tasteless thing to do.

On Aug. 19 Polanski called a press conference to defend his wife’s honor, and his own. (He was still years away from the sexual assault scandal that prompted him to flee the U.S. and never return.)

Calling Sharon “beautiful” and a “good person,” he said, “the last few years I spent with her were the only time of true happiness in my life.”

Sarah Morris/Getty Images

Tate’s mother, Doris, spent the rest of her life as an advocate for the rights of victims and their families, and Debra, for years the de facto spokesperson for the family, has been committed to seeing that her sister’s killers remain in prison.

Manson, Atkins, Watson, Krenwinkel and Leslie Van Houten, who participated in the LaBianca killings, were originally all sentenced to death, but a temporary moratorium on the death penalty in California in 1972 resulted in their sentences being converted to life in prison.

Atkins died of cancer in 2009. Van Houten was recommended for parole in 2016 and 2017, but then-Gov. Jerry Brown refused. Manson, who never stopped spouting his half-cocked theories about race wars and whatever else was grinding his gears, died in November 2017.

Of the three movies this year featuring a portrayal of Tate, Tarantino’s inclusion of her and Manson as characters is the most mysterious, and perhaps most peripheral to the main plot, as the story has been described as being more about 1969 than the murders. “I’m barely on set with them,” Robbie said about leads Brad Pitt and Leonardo DiCaprio, who play her next-door neighbors.

Harron’s film is mainly about how Manson, played by Matt Smith of The Crown and Doctor Who fame, manipulated his “family” members. The Haunting of Sharon Tate, meanwhile, is all about her, but uses true events as a jumping-off point.

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

And it’s too far of a leap, for some.

Debra Tate has voiced her displeasure with the movie’s concept, which is that the doomed actress was receiving subliminal messages and foresaw her fate, and that of her friends. The filmmakers purport to have been inspired by an interview Tate gave in 1968, in which she mentioned having a dream about being murdered by cult members.

“It doesn’t matter who it is acting in it—it’s just tasteless,” Debra told People in 2018. “It’s classless how everyone is rushing to release something for the 50th anniversary of this horrific event.”

“I know for a fact she did not have a premonition—awake or in a dream—that she and Jay would have their throat cut,” she added. “I checked with all of her living friends. None of her friends had any knowledge of this. Tacky, tacky, tacky.”

But Duff, who hasn’t said much about the film leading up to its theatrical release Friday, shared the trailer on Instagram. And she wrote a year ago, “Had the incredible opportunity of playing Sharon Tate the past two weeks in an independent movie. She was an amazing woman and it was a true honor.”