Jean Seberg spent the 1960s as an internationally recognized actress, an icon of French cinema’s New Wave and one of the chicest women in Hollywood, or New York, or Paris.

The 1970s were far less kind, and by the end of the decade, she was gone, dead of a “probable suicide.”

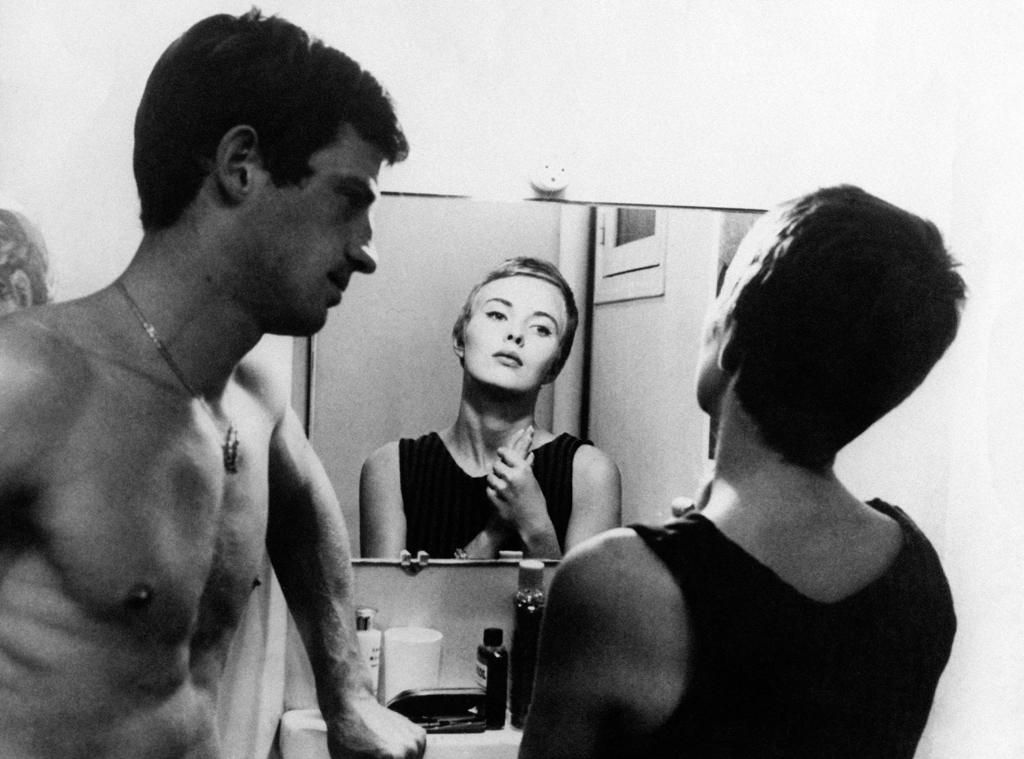

At a glance, the tragedy that was Seberg’s heady rise and ultimate descent into drug addiction and mental illness makes up the majority of her legacy—that, and her legendary turn in Jean-Luc Godard‘s 1960 classic Breathless, playing Patricia, the dubiously loyal American girlfriend of Jean-Paul Belmondo‘s doomed criminal Michel.

Seberg seeks to re-inject the humanity into what was truly a stranger-than-fiction life story.

“Well, I had this general perspective of her that coincided with the broad perspective, which is ‘chick from Breathless in the ’60s, became a little eccentric, moved to Paris and never wanted to move back, drank herself to oblivion and ended her life,'” Kristen Stewart, who plays the actress in the film, which started streaming on Amazon Prime Video on Friday, told Awards Watch in December.

“It’s just such an absurd plot line for what actually transpired in Jean’s life,” she continued, “and I think that her story is quite urgent, considering this subjugation of the truth and this maddening relationship we have with the truth in media and the idea that a woman who had a perspective which felt threatening to the government at large.

“She was sort of exiled illegally, not for breaking the law, but just for having an opinion that didn’t coincide with theirs. So that in itself is terrifying, that we actually think, in a broad sense, that she was just this kooky actress who moved away and drank herself to s–t. I mean, this woman really went through a lot and it was really violent, and I think that’s absolutely a story worth telling.”

Incidentally, Stewart and director Benedict Andrews also said at the Toronto International Film Festival that there were times during filming when they could sense Seberg’s presence on set.

“Any time there was a cat going running cross the set, anytime something strange happened, it felt spooky, ghostly,” Stewart said. “There was s–t going down that didn’t make sense and I felt, there she is.”

While the finer details of Seberg and some of its most intimate moments are more of the based-in-truth variety, the cold facts of the matter aren’t any less shocking.

And, as Stewart—a former child star turned tabloid magnet and cinema and fashion darling who remains politically outspoken, despite her own wariness toward about sharing too much of herself with the world—pointed out, it remains an unfortunately timely story to tell.

“Something in me is not equipped to be in America and play those games, selling yourself over martinis, being charming and gay and bright. It’s not worth the fight,” Seberg told the New York Times in 1974. “They always transform you into everything you aren’t.”

United Artists/Kobal/Shutterstock

Seberg spent much of her short life in France, so folks could be forgiven for forgetting that she was born in small-town Iowa, the daughter of a substitute teacher and a pharmacist. She had an older sister and two younger brothers, the youngest of whom was killed in a car accident at 18, in 1968.

After doing some summer stock theater, Seberg enrolled at the University of Iowa for a semester, but ended up getting her big break when Otto Preminger—the taboo-courting director of Laura and The Man With the Golden Arm who could also be a bully, especially toward his female stars—picked her angelic face out of thousands of other entries in a talent search that Seberg’s high school drama coach had volunteered her for without her even knowing.

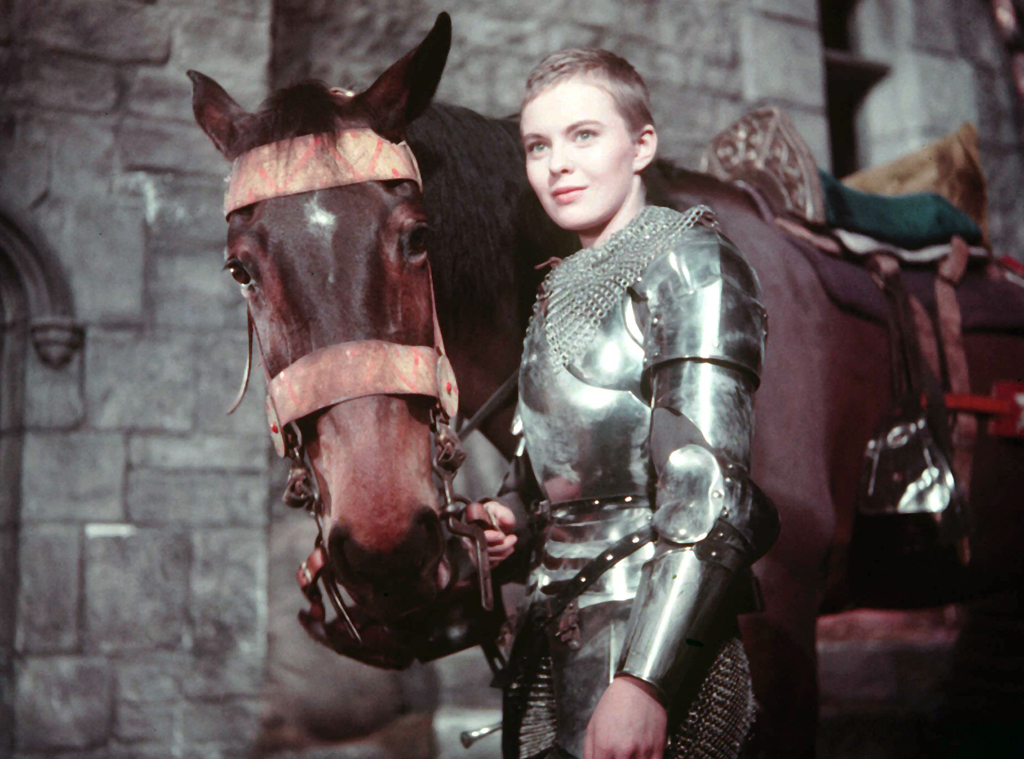

And so Seberg made her film debut at 17, playing Joan of Arc in Preminger’s 1957 drama Saint Joan, adapted from the George Bernard Shaw play—a project that for its day and age was wildly hyped in advance, thanks in no small part to the newcomer in the starring role.

Critics largely panned her performance, prompting Seberg’s remark, “I am the greatest example of a very real fact, that all the publicity in the world will not make you a movie star if you are not also an actress.”

Rialto Pictures/StudioCanal

“I have two memories of Saint Joan,” she later said. “The first was being burned at the stake in the picture. The second was being burned at the stake by the critics. The latter hurt more. I was scared like a rabbit and it showed on the screen. It was not a good experience at all. I started where most actresses end up.”

Preminger liked her, though, and cast her in his next movie (and two more after that), 1958’s Bonjour Tristesse, which they shot in Paris. And there Seberg stayed, having fallen in love with lawyer and aspiring filmmaker François Moreuil. They married in September 1958, when she was 19.

Mondadori Portfolio via ZUMA Press

In 1960 she starred with Belmondo in Breathless, one of the most well-known films of the French New Wave movement, which also established her as an It Girl and launched countless style imitators, from the top of her gamine pixie cut to the tips of her ballet flats.

Seberg split up with Moreuil but she still agreed to be in his directorial debut, 1961’s Love Play.

Though Seberg and the city of Paris became inextricably linked, she didn’t consider herself an expatriate.

Columbia/Kobal/Shutterstock

“I’m in Paris because my work has been here,” she explained to a reporter in the 1960s. “I will go where the work is. The French life has its drawbacks. One of them is the formality. The system seems to be based on saving the maximum of yourself for those nearest you.

“Perhaps that is better than the other extreme in Hollywood, where people give so much of themselves in public life that they have nothing left over for their families. Still, it is hard for an American to get used to.”

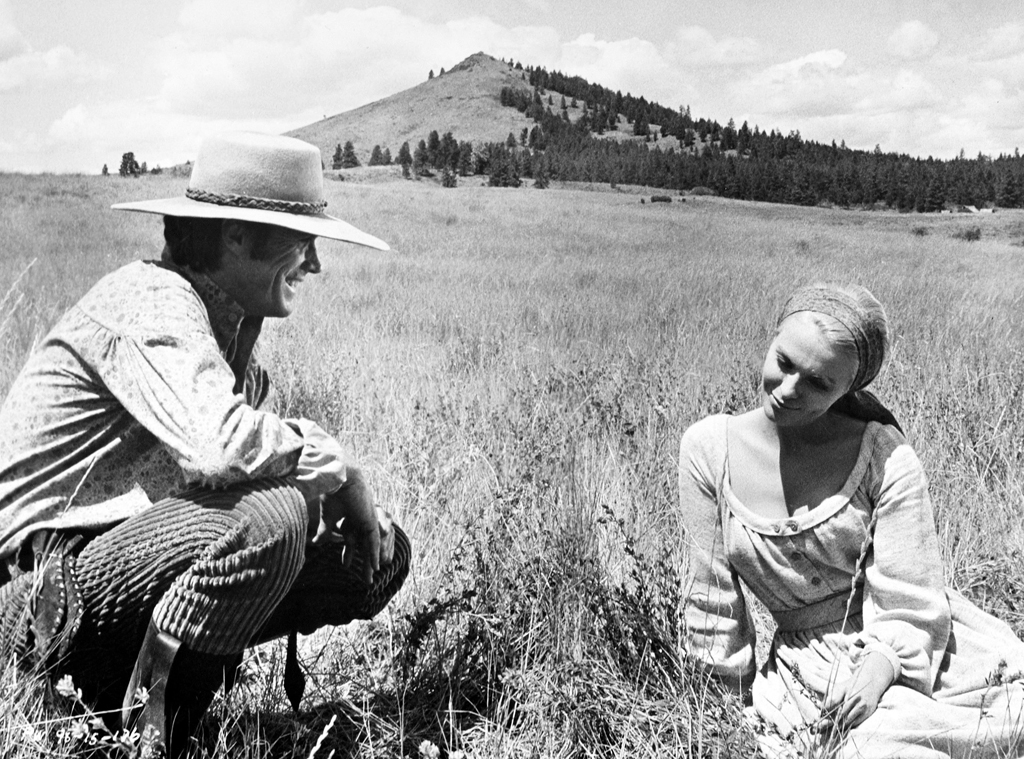

While she did a number of French films, working with the likes of Claude Chabrol and Jean Becker, she did go where the jobs were, including 1964’s Lilith, with Warren Beatty, for which she earned her sole Golden Globe nomination, and the 1969 musical Paint Your Wagon, which reportedly resulted in her having an affair with costar Clint Eastwood.

PARAMOUNT PICTURES / Album

The main constant amid the highs and lows of her storied career was that her personal life remained… complicated.

Seberg had married filmmaker, writer, diplomat and former French Resistance member Romain Gary, who was 24 years her senior, in October 1962, about a month after his divorce from his first wife was finalized—and three months after Seberg gave birth to their son, Alexandre Diego Gary, in Barcelona.

Gary remained protective of Seberg throughout their life together and apart, eventually becoming a firsthand witness to what turned out to be her government-mandated decline.

In early 1970, Seberg had an affair with a student activist, Carlos Navarra, while on location in Mexico and prematurely gave birth to a daughter, Nina Hart Gary (he was already estranged from his wife by then, but Romain Gary maintained publicly that he was the child’s father) on Aug. 23, 1970.

The baby died two days later and Seberg had her transported to her hometown of Marshalltown, Iowa, for burial.

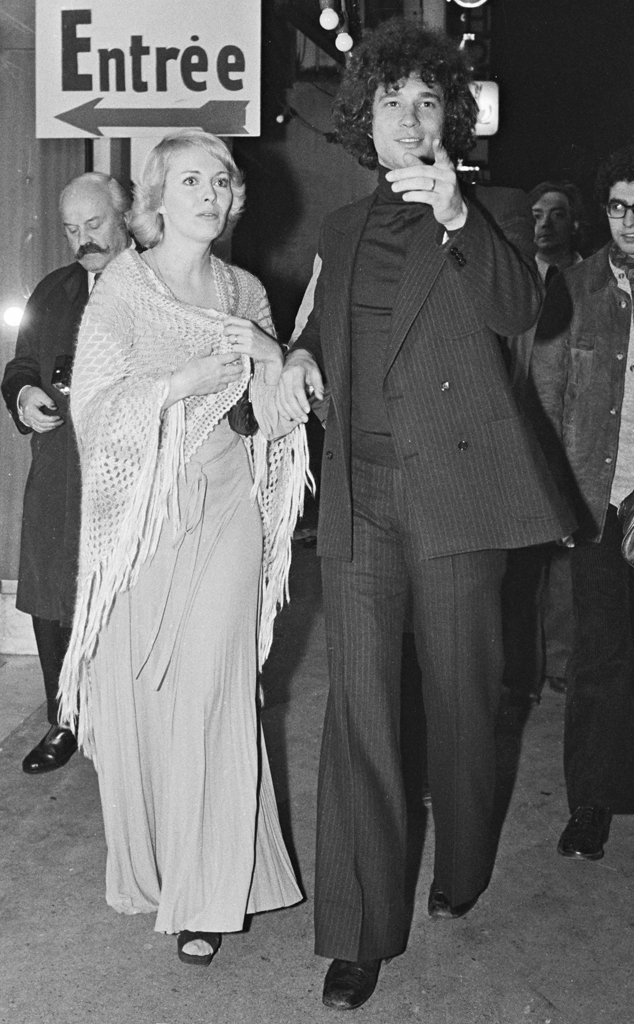

Seberg and Gary divorced and she married producer Dennis Berry in 1972. They hosted regular soirees at their Left Bank apartment (in the same complex where Gary still lived with their son), their guests a parade of artists and assorted thinkers of varying success. She told Berry on New Year’s Eve, 1973, “I’m going to live this year as if were my last. I like to have friends laughing around me, and I like good food and good wine—so what I’m the only one who can afford to pick up the check?”

Seberg told the New York Times in 1974 that she had “cracked up” after the loss of her baby. But “if you keep busy, you don’t go crazy.”

Meanwhile, Seberg’s longtime left-wing political leanings (she joined the Des Moines chapter of the NAACP when she was 14), including her prominent financial support for the Black Panther Party, had attracted the attention of the U.S. government, which still under the leadership of decades-spanning Director J. Edgar Hoover was busy waging a counterintelligence war against the Panthers and other anti-establishment groups, painting them broadly as violent radicals and seeking to discredit them by any means possible.

A rumor that took wing in 1970—first via a blind gossip item published in the Los Angeles Times—that it was an affair with a Panther that had resulted in Seberg’s pregnancy, was part of just one of the FBI’s countless insidious COINTELPRO projects.

According to the 1981 biography Played Out: The Jean Seberg Story, Seberg did indeed have romantic relationships with activist Hakim Jamal (played by Anthony Mackie in the film), who was shot to death in 1973, and Black Panther Party leader Raymond ”Masai” Hewitt—the latter of whom the FBI speculated was the father of Seberg’s baby. Both men were married. Hewitt died in 1988.

Seberg told the NY Times in 1974 that she had once been very committed to the Panthers, but had “officially broke with them…I’ve analyzed the fact that I’m not equipped to participate absolutely and totally. I had a very, very bad mental breakdown, and now I realize I wouldn’t want a person like me in a group I was a member of, as Groucho Marx would put it.”

Then 35, she noted, “I’m in a funny age bracket for an actress. I’m not young enough to play the ingenue any more, and I’m not old enough to get into the character thing. It is perhaps for your own sanity that you go into other areas.”

Seberg also said, “If you want to know what I’ll be doing 10 years from now, I couldn’t say. It’s like asking a woman whether she will be graceful at 45. Who knows what life will do to you?”

Bertrand Rindoff Petroff/Getty Images

Seberg continued to work, appearing in the likes of the 1970 disaster thriller Airport and 1971’s Kill! Kill! Kill! Kill!, directed by Gary; and 1975’s The Big Delirium, directed by Berry. She also directed her own short, 1974’s Ballad for Billy the Kid, but her career decidedly slowed down. Her final screen appearance was in the 1976 film The Wild Duck.

She also continued to drink, heavily, and became increasingly paranoid that she was being watched, that government spies were following her and tapping her phone. She spent time in institutions receiving psychiatric care.

Seberg and Berry split up and, in 1979, she got together Ahmed Hasni, an Algerian actor with whom she spent a few unhappy months (he called her his wife but they weren’t legally married).

Silver Screen Collection/Archive Photos/Getty Images

Hasni would later tell reporters that he last saw his wife on the night of Aug. 30, 1979, that they had gone to bed after going to the movies and she seemed fine, but when he woke up the next morning she was gone. “She took nothing but her papers, a blanket, her barbiturates and a bottle of water,” he said.

Seberg’s body was found on Sept. 8 in an upscale neighborhood in Paris’ Right Bank. She was in the backseat of her white Renault, wrapped in her blanket, and she appeared to have been dead for days. Police felt that the car couldn’t have been parked where it was for the entire nine days without attracting notice, that it was likely moved there closer to when she was found.

Her death was ruled a probable suicide by barbiturate overdose. A note was found in the car, reading in part, “I can’t live any longer with my nerves,” and asking her son to forgive her, encouraging him to “be strong.”

She was 40.

Hasni told reporters that Seberg had attempted suicide in August by jumping in front of a Métro train.

“I knew she wanted to kill herself,” he said. “For some time she didn’t want to see anybody.”

Two days after she was found, Gary held a news conference in Paris, where he stated firmly, “Jean Seberg was destroyed by the FBI. In 1970, when we were in the process of getting a divorce, this agency apparently gave a large American newspaper information indicating Jean was pregnant with a child whose father was a leader in the Black Panthers.”

A few days later, the FBI admitted to planting the gossip item, part of a concerted effort to “cheapen” Seberg’s image and hopefully deter other “friends of the Black Panthers” from getting too involved with the group.

Someone at the FBI first came up with the idea in April 1970, knowing Seberg was pregnant, but he was encouraged to wait until she was more obviously showing.

A bureau official wrote (in documents obtained by the Los Angeles Times in 1979), “Jean Seberg has been a financial supporter of the BPP and should be neutralized. Her current pregnancy by [censored] while still married affords an opportunity for such effort.”

After getting the go-ahead from Hoover himself, they started with a message drafted to a Hollywood gossip columnist, purportedly a first-person account of seeing Seberg in Paris “heavy with baby” and the actress “confided the child belonged to [censored name] of the Black Panthers…The dear girl is getting around! I thought you might get a scoop on the others.”

The blind item was first published on May 19, 1970, by Joyce Haber at the LA Times, Haber referring to Seberg as “Miss A,” who was “pursuing a number of free-spirited causes, among them the black revolution. She lived what she believed, which raised a few Establishment eyebrows. Not because her escorts were often black, but because they were black nationalists.”

Contacted after Seberg died, Haber said she had received the tip from a “reliable source” and preferred not to comment on whether she had reached out to the actress herself.

Newsweek advanced the tidbit in its Aug. 24, 1970, issue, identifying Seberg and reporting that she and Gary were back together “even though the baby that Jean expects in October is by another man—a black activist she met in California.” (The magazine quoted Seberg, who had been recuperating at a hospital on Majorca from a pregnancy-related issue, saying she and Gary were “completely reconciled.”)

She was so distraught when she read the item that she immediately went into labor, nine weeks early, according to Romain Gary.

“Jean became psychotic,” he said at the news conference. “Every year on the anniversary of this stillbirth she has tried to take her own life.” He maintained that the baby had been white and that he was the father.

Seberg had told the Times, “We opened the coffin and took 180 photographs, and everybody in Marshalltown who was curious what color the baby was got a chance to check it out. A lot of them came to look.” She and Gary sued Newsweek for libel damages in 1971 and settled for around $8,000, Seberg claiming in the lawsuit that she had suffered a “physical and moral shock which caused a premature birth.”

Perhaps one thing to be appreciative of is the Freedom of Information Act, which made it possible for newspapers to get their hands on documents that proved there was a plot against Jean Seberg.

Reporting on Seberg from her hometown of Marshalltown, Iowa, after the FBI’s actually villainous (not to mention racist and misogynistic) actions had come to light, the John McCormick wrote of the fallen star in the LA Times:

“People here don’t speak of Seberg simply as the movie actress who left home to play Joan of Arc and others. They think of her as a latter-day warrior in her own right, a small-town innocent who chased her destiny, fought her good fight, then got herself martyred at the stake.”

Carol Hollingsworth, the drama coach who had entered Seberg in Preminger’s talent search barely 25 years beforehand, told McCormick, “Jean was a lovely, talented girl. I wasn’t the only one who recognized her talent. You see, she wanted this career from childhood. But it’s all turned out so sad.”

Seberg is streaming now on Amazon Prime Video.